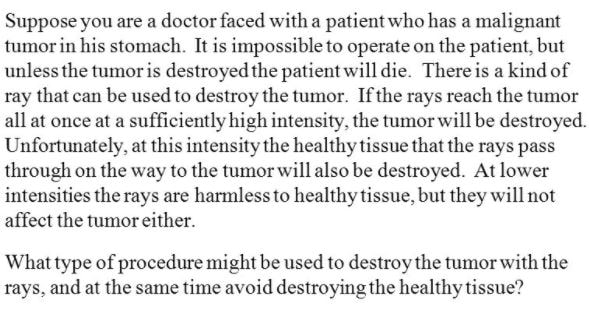

This is usually called the problem of transfer, and a classic laboratory problem was devised by Mary Gick & Keith Holyoak.

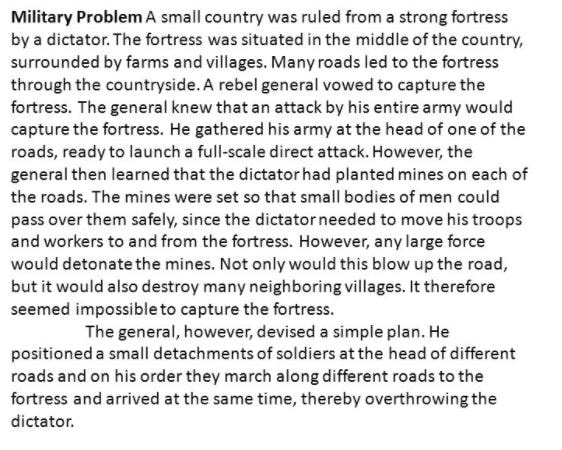

This problem has proven very difficult to solve. One promising solution is to give subjects something to do that forces them to focus on the underlying structure of the problem. The underlying structure in the example above is "to avoid collateral damage, disperse your forces and converge at the point of attack." The underlying structure is expressed with tumors and rays in the problem and via a fortress and armies in the story.

Dedre Gentner and her collaborators have tried (with some success) to improve transfer by asking people to compare problems. When you compare problems with the same deep structure, that obviously focuses attention on that deep structure and so you'll remember it better later.

A disadvantage of comparison is that the instructor must provide parallel versions for all problems. Ricardo Minervino and his colleagues sought a technique that would provide similar benefits, but might be more applicable to classroom situations.

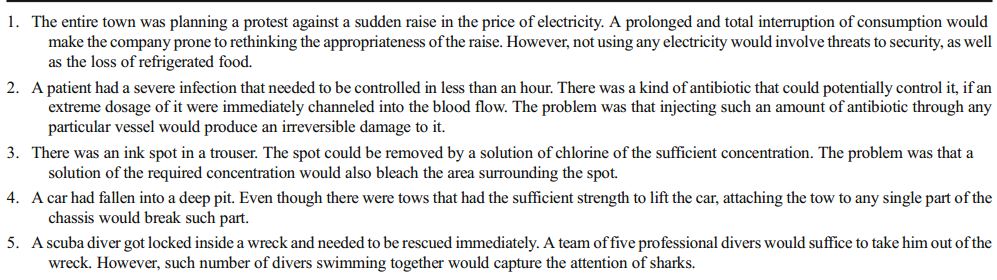

In their experiment, subjects first read the fortress-army story (along with two other stories). At transfer, everyone was asked to solve the tumor-rays problem, but one group was also first asked to invent an analogous problem. Examples of the problems subjects invented appear below:

The experimenters also showed that it wasn't just the deeper thought required by the problem creation that made those subjects more likely to get the problem right. Another control group was given the tumor-rays problem and were asked to create an analogous problem before solving it, but they did not read the fortress-army story beforehand. Just 10% of these subjects solved the radiation problem.

In terms of the psychological mechanism behind this effect, it's not a huge surprise. Again, it's a technique that prompts people to focus attention on the deep structure, just as comparison does. What's nice about this technique is that, as the authors note, it removes the burden from the instructor to devise parallel problems. But that also gives students the freedom to create an "analogous" problem that isn't really analogous. So the instructor needs to check up on the problems students create.

Still, it's useful to know about the consequences when students create a new problem, and teachers may find it useful in some contexts

RSS Feed

RSS Feed