This pattern of performance is especially troubling, given that multitasking--especially media multitasking--is becoming more prevalent, especially among younger people.

But there's no evidence that doing a lot of media multitasking makes you better at it. In one study, researchers (Ophir, Nass & Wagner, 2009) found that college students who reported more habitual multitasking were actually less skillful in standard laboratory tasks that require shifting or switching attention.

Why would they be worse? One possibility is that they are biased to spread attention broadly. That's a poor strategy when you're confronted with two tasks that have different or even conflicting requirements. But that bias would make you more likely to multitask, even if it's not very effective.

Whether multitasking creates that bias or whether that bias exists for other reasons and prompts people to multitask is not known.

Either way, if heavy multitaskers have a bias to spread attention broadly, that bias should be helpful in tasks where two different streams of information are mutually supportive.

A new study (Lui & Wong, 2012) tests that prediction.

The researchers used the pip and pop task. Subjects view a display like this one:

All of the lines alternate colors (red and green) but do so asynchronously. The interesting feature of this task is that every time the target changes color, there is an auditory signal--the pip. The pip doesn't tell you where the target is, the color, or whether it's horizontal or vertical. It just corresponds to the color change of the target.

Subjects are not told that the pips have anything to do with the visual search task, nor that they should pay attention to the pips.

But people who integrate the visual information with the auditory report that the target seems to pop out of the display. They feel like they don't need to laboriously search, they just see it.

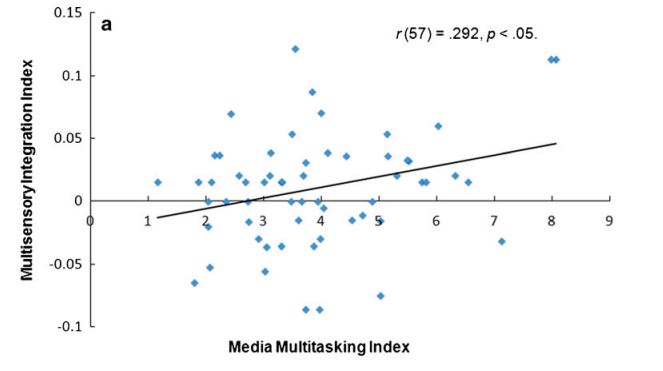

The researchers compared subjects speed and accuracy in finding the target when the auditory signal was present and found that accuracy (but not speed) correlated with subjects' self-reported frequency of multitasking, as shown below. Not a huge effect, but reliable.

Does this have any bearing on the types of tasks people do outside of the lab?

Information in two different tasks is presumably uncorrelated. When two different streams of information are mutually reinforcing it's by design--the audio and visual portions of a movie, for example. In such cases it's so well synchronized that people make few errors.

One way that multitaskers might have an advantage in real-world tasks is in the detection of unexpected signals. For example, if you're biased to monitor sounds even as you're writing a document, you might be more likely to perceive an auditory signal that an email has arrived in a noisy office environment. Or even to perceive a police siren or lights while driving. Such predictions have not, to my knowledge, been tested.

Lui, K. F. H & Wong, A. C.-N (2012) Does media multitasking always hurt? A positive correlation between multitasking and multisensory integration. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 19, 647-653

Ophir, E., Nass, C., & Wagner, A. D. (2009). Cognitive control in media multitaskers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106,15583–15587

RSS Feed

RSS Feed