A prototypical experiment looks like this (rows = subject groups; columns = phases of the experiment).

A consistent finding is that the benefit to memory is larger if the test is harder. But of course if the test is harder, then people might be more likely to make mistakes on the test in Phase 2. And if you make mistakes, perhaps you will later remember those incorrect responses.

But data show that, even if you get the answer wrong during Phase 2 you'll still see a testing benefit so long as you get corrective feedback. (Kornell, Hays & Bjork, 2009).

A tentative interpretation is that you get the benefit because the right answer is lurking in the background of your memory and is somewhat strengthened, even though you didn't produce it.

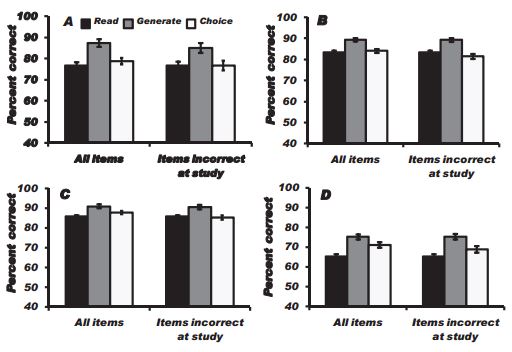

So that implies that the testing effect won't work if you simply don't know the answer at all. Suppose, for example, that I present you with an English vocabulary word you don't know and either (1) provide a definition that you read (2) ask you to make up a definition or (3) ask you to choose from among a couple of candidate definitions. In conditions 2 & 3 you obviously must simply guess. (And if you get it wrong I'll give you corrective feedback.) Will we see a testing effect?

That's what Rosalind Potts & David Shanks set out to find, and across four experiments the evidence is quite consistent. Yes, there is a testing effect. Subjects better remember the new definitions of English words when they first guess at what the meaning is--no matter how wild the guess.

Guessing by picking from amongst meanings provided by the experimenter provides no advantage over simply reading the definition. So there is something about the generation in particular that seems crucial.

This account is speculation, obviously, and the authors don't pretend it's anything else. I wish that they were equally circumspect in their guess at the prospects for applying this finding in the classroom. Sure, it's an important piece of the overall puzzle, but I can't agree that "this line of research is relevant to any real world situation where novel information is to be learned, for example when learning concepts in science, economics, politics, philosophy, literary theory, or art."

The authors in fact cite two other studies that found no advantage for generating over reading, but Potts & Shanks think they have an account for what made those studies not very realistic (relative to classrooms) and what makes their conditions more realistic. They may yet be proven right, but college students in a lab studying word definitions is still a far cry from "any real world situation where novel information is to be learned."

The today-the-classroom-tomorrow-the-world rhetoric is over the top, but it's an interesting finding that may, indeed, prove applicable in the future.

References:

Agarwal, P. K., Bain, P. M. & Chamberlain, R. W. (2012). The value of applied research: Retrieval practice improves classroom learning and recommendations from a teacher, a principal, and a scientist. Educational Psychology Review, 24, 437-448.

Kornell, N., Hays, M. J., & Bjork, R. A. (2009). Unsuccessful retrieval

attempts enhance subsequent learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 35, 989–998

Potts, R., & Shanks, D. R. (2013, July 1). The Benefit of Generating Errors During Learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. Advance online publication. doi:10.1037/a0033194

RSS Feed

RSS Feed