Here is the nub of his argument:

Point 1: The author points out that some conclusions have more data behind them than others: initially, Higgs suggested something like the boson might exist. Today, there are many more data consistent with the boson and its suggested characteristics.

Point 2: The best supported conclusions of the core natural sciences (physics, chemistry, biology) are well established, but the best developed social science (he cites economics as an example) “have nothing like this status” in terms of the reliability of their findings.

Point 3: “While many of the physical sciences produce many detailed and precise predictions, the social sciences do not. The reason is that such predictions almost always require randomized controlled experiments which are seldom possible when people are involved.”

Point 4: He closes by suggesting that results from social sciences not be ignored, but that we must recognize their limitations. “At best, they can supplement the general knowledge, practical experience, good sense and critical intelligence that we can only hope our political leaders will have.”

There are several significant problems here.

Point 1: Gutting is right. Better supported conclusions are more reliable.

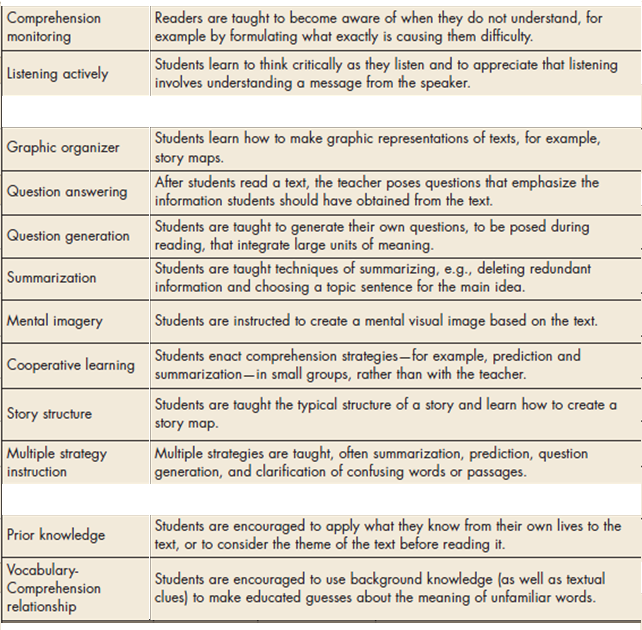

Point 2: Gutting argues that findings from social sciences are less reliable than those of natural sciences, and so should not be trusted. First, if our goal is to use science to inform public policy (his stated goal) then the question is whether social science findings add value compared to not having the findings in hand. It doesn’t really matter if they are as good as some other science. Second, on the point of reliability, Gutting is wrong. Some findings in social sciences are known with a high degree of reliability, e.g., the consequences of schedules of practice on memory.

On this point and point 3, Gutting paints with an extraordinarily broad brush, seeking to characterize the nature of “social sciences” in general, and to contrast them with all of the “natural sciences.”

Point 3: Regarding the use of random control designs, Gutting is again in error. Most of the experiments I have done in my career have been laboratory studies using random control designs. Readers of this blog are of course aware that many studies in education use this design. Gutting also fails to note that some areas of biology (e.g., evolutionary biology) and of physics (e.g., astrophysics) make extensive use of data that are not produced by randomized control trials.

Point 4: Inviting data from social sciences to “supplement” good old common sense is tantamount to inviting people to ignore the data, or more likely to interpret the data as consistent with their beliefs, a phenomenon described by social scientists.

I am suspicious that this post was written as part of an experiment by nefarious social scientists to see how readers of the Times would react.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed