Please note: A few people have told me that they have trouble finding my column on RealClearEducation.com. If you would like an email notification when I post a new column, please just email me, and I'll ping you when I post.

You often hear the phrase that small children are sponges, that they constantly learn. This sentiment is sometimes expressed in a way that makes it sound like the particulars don’t matter that much; as long as there is a lot to be learned in the environment, the child will learn it. A new study shows that for one core type of learning, it’s more complicated. Kids don’t learn important information that’s right in front of them, unless an adult is actively teaching them.

The core type of learning is categorization. Understanding that objects can be categorized is essential for kids’ thinking. Kids constantly encounter novel objects; for example, each apple they see is an apple they’ve never encountered before. The child cannot experiment with each new object to figure out its properties; she must benefit from her prior experience with other apples, so that she can know, for example, that this object, since it’s an apple, must be edible.

But how can a child tell which properties of the apple are incidental (e.g., it has a long stem) and which properties are true of all apples (it’s edible)? The child must ignore many incidental properties, and hold on to the important properties that are true of all apples.

Previous research shows that by age three or four, children are sensitive to linguistic cues about this matter. They appropriately attach significance to the difference between “This apple has a long stem” and “Apples are good for eating.” “This apple” signifies that the information provided applies only to this particular apple; “Apples” indicates a generalization about all apples.

A recent study (Butler & Markman, 2014) examined whether there are cues outside of language that guide children in resolving this problem. The researchers tested the possibility that children are sensitive to adults teaching them; if an adult deliberately highlights a property for the child’s benefit, that presumably is a property of some importance, and one that is characteristic of all objects of this sort.

Children (aged 4-5) were shown a novel object and were told that it was a “spoodle.” There was a brief test to be sure that the child got the name right, and then another, irrelevant task. The experimenter began to clean the materials from this other task, and this is when the special property of the spoodle came into play; spoodles are magnetic.

In the pedagogical condition, the experimenter said “Look, watch this” and used the spoodle to pick up paperclips. In the intentional condition, the experimenter used the spoodle to pick up paperclips, but did not request the child’s attention or make eye contact. In the accidental condition, the experimenter feigned accidentally dropping the spoodle on the clips. In all of the conditions, the experimenter held the spoodle with the paper clips clinging to it and said “wow!”

Next, the child was presented 16 objects and was asked to say which were spoodles. Half were identical to the original spoodle, and half were another color. In addition, half of each color were magnetic and half were not.

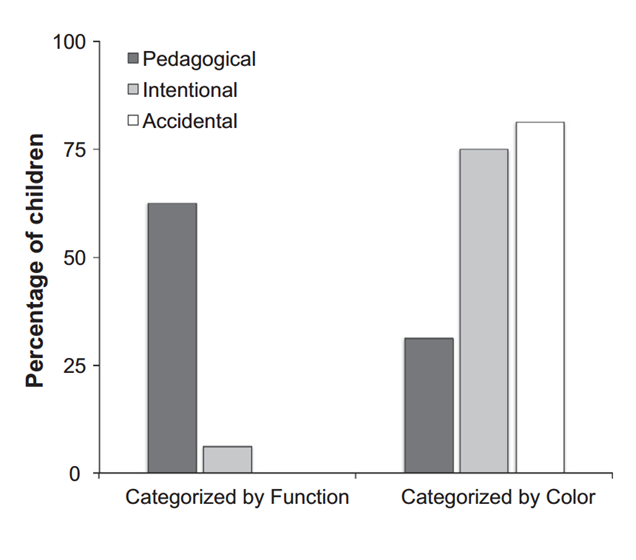

So the question is which property kids think makes an object a spoodle: appearance (i.e., color) or function (i.e., magnetism). The data are shown here:

Yet when the adult did the exact same thing, but also made plain to the child her actions were for the child’s benefit, that she was teaching, then the child understood that magnetism held special significance for spoodle-hood.

I think this study has an interesting implication for differences in kids’ preparedness for schooling, associated with their home environment. We tend to focus on differences in the richness of experiences available to kids. That’s important, but this experiment provides a concrete example of small differences in parenting may have important consequences for children’s learning. “Little sponges” don’t learn certain types of information, even in a rich environment. They have to be taught.

Reference:

Butler, L. P., & Markman, E. M. (2014). Preschoolers use pedagogical cues to guide radical reorganization of category knowledge. Cognition, 130, 116-127.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed