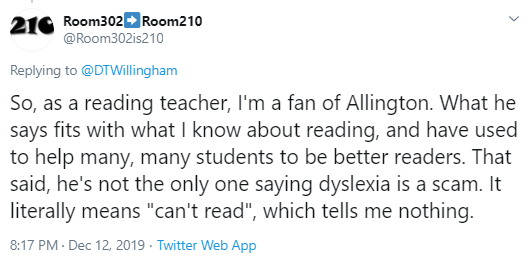

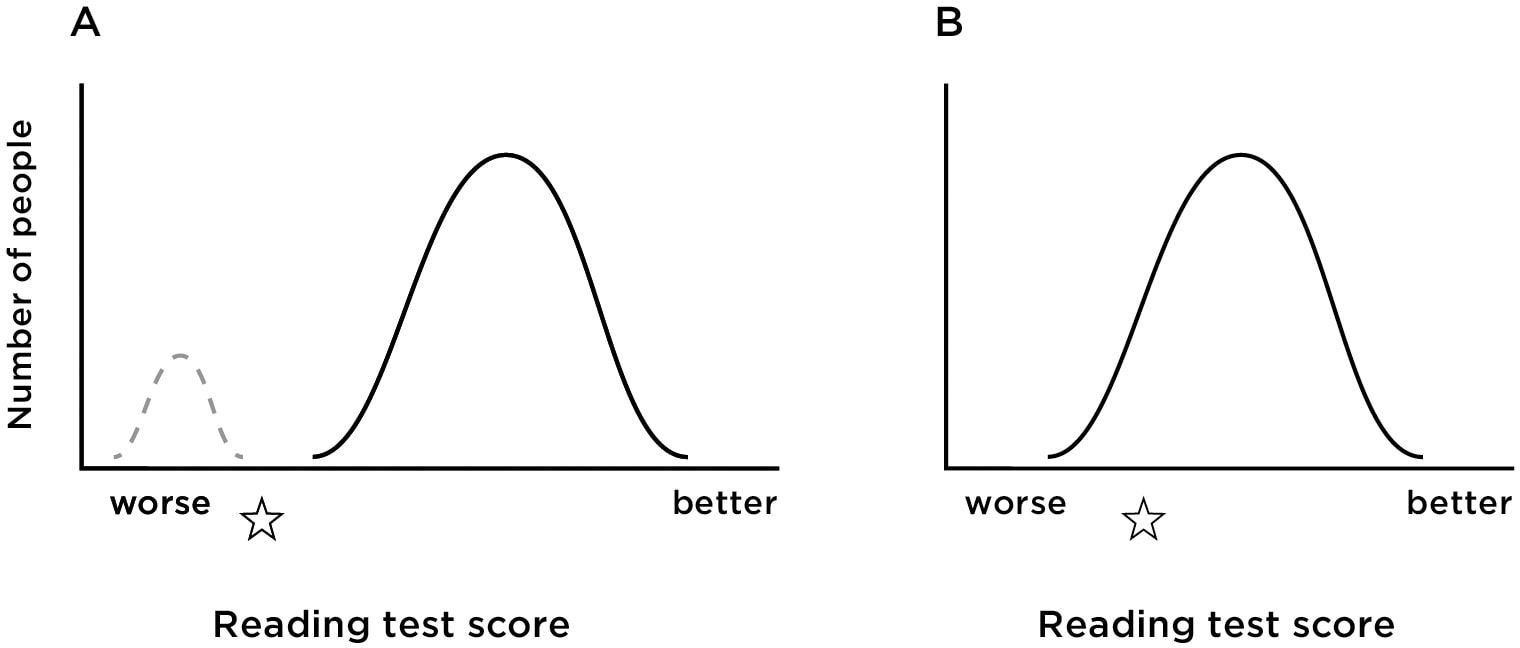

Presumably, we’re going to measure a child’s reading proficiency with a test, and a score below some cut-off will make us suspicious that the child is having a specific reading disability. Sounds simple enough, but there’s a problem. The figure shows two graphs depicting imaginary data from 10,000 first graders. In panel A, there’s a bell curve on the right, which we would call typical readers and then to the left a smaller number of readers who are impaired. There’s no mistaking that this second group is different than the first, so choosing a cut point—a point at which you say “score below here, and you probably have dyslexia” is straightforward; I’ve marked it with a star.

So is dyslexia even real? Maybe it’s more accurate to say “these are the kids in the bottom 10% (or whatever) on this measure.” Why label them “dyslexic?”

Although any cut score will lead to some errors, it’s not the case that it’s a completely arbitrary line. There is something different about many of the kids in the left tail of the graph. That’s important because it makes us want to be more active. Saying “well, there’s always going to be someone who is the worst at reading” sounds like we’ve given up. But if you accept that the child is facing special challenges, it invites searching for a solution. So what makes us think kids with dyslexia are different than typical kids?

First, there is a genetic component. The incidence of dyslexia in the population is about 9%. But if a child has a parent with dyslexia, the chances the child will too are about 35 or 40%. (Pennington et al., 1991). Of course, that high figure may be a consequence of the dyslexic parent offering a less supportive literacy environment than other parents do. Better evidence comes from studies comparing identical and fraternal twins. Twins of each type are likely to attend the same school and be exposed to similar home environments, but identical twins share 100% of their genes, and fraternal twins only 50%. If a child has dyslexia her fraternal twin has a 38% chance of having it too. But an identical twin has a 68% chance of having it (Defries & Alarcón, 1996). Of course the fact that there is a genetic contribution doesn’t mean that ones genes amount to an inevitable reading destiny. Children with dyslexia can become good readers—it will just take more work.

Here’s another reason to think that dyslexia is real: kids show subtle signs of a problem before reading instruction begins (e.g., Guttorm, Leppanen, Richardson, & Lyytinen, 2001; Lyytinen et al., 2004; Richardson, Kulju, Nieminen, & Torvelainen, 2009). These studies examine children from families where one of the parents has dyslexia. Researchers test how these children hear and use language when they are quite young, and then wait for them to get older. Then they note which children struggle with reading and which do not and look back at the data collected when they were younger. The two groups show differences very early in life. At birth, the parts of their brain that handle sounds show different responses to human speech. At age two and a half, children who would later have difficulty learning to read speak in shorter, less syntactically complex sentences, and their pronunciation is less accurate. At age three, they have a smaller vocabulary. At age five, they show deficits in phonological awareness, and they know the names of fewer letters.

A third point regarding the “reality” of dyslexia; we know that it’s not simply a delay, a byproduct of the fact that kids develop at different rates. There’s no doubt that some children learn to read faster than others, but kids identified with dyslexia don’t catch up without intervention. The kids who read poorly in early elementary school continue to struggle unless they get help (Scarborough & Parker, 2003; Shaywitz et al, 1995). Children with a disability can grow up to be good readers but even they show residual problems like slower single-word recognition and problems with spelling (Bruck, 1990; Maughan et al, 2009).

So here’s the way I think about the “reality” of dyslexia. It’s not a disease in the sense that measles is a disease; you have it or you don’t. Rather, we start with the theoretical claim that reading ability is a product of the home environment, teaching at school, and some ability-to-learn that is within the child. Dyslexia is a problem in the child’s ability to learn (restricted to reading and closely related to other language tasks). The three findings I’ve just listed are consistent with the idea that some children do have a specific ability-to-learn problem; but that doesn’t mean the problem is present or absent. The severity of the problem runs on a continuum, so in that way it’s more like high blood pressure or obesity. And like those problems, the fact that there’s not an obvious cut-point at which you can say “you have the disease, but you don’t” doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t take it seriously.

References

Bruck, M. (1990). Word-Recognition Skills of Adults With Childhood Diagnoses of Dyslexia. Developmental Psychology, 26(3), 439–454.

DeFries, J. C., & Alarcón, M. (1996). Genetics of specific reading disability. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 2(1), 39-47.

Guttorm, T. K., Leppanen, P. H. T., Richardson, U., & Lyytinen, H. (2001). Event-Related Potentials and Consonant Differentiation in Newborns with Familial Risk for Dyslexia. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 34(6), 534–544.

Lyytinen, H., Aro, M., Eklund, K., Erskine, J., Guttorm, T., Laakso, M.-L., … Torppa, M. (2004). The development of children at familial risk for dyslexia: birth to early school age. Annals of Dyslexia, 54(2), 184–220.

Maughan, B., Messer, J., Collishaw, S., Pickles, A., Snowling, M., Yule, W., & Rutter, M. (2009). Persistence of literacy problems: spelling in adolescence and at mid-life. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(8), 893–901.

Pennington, B. F., Gilger, J. W., Pauls, D., Smith, S. A., Smith, S. D., & DeFries, J. C. (1991). Evidence for major gene transmission of developmental dyslexia. JAMA, 266(11), 1527-1534.

Richardson, U., Kulju, P., Nieminen, L., & Torvelainen, P. (2009). Early signs of dyslexia from the speech and language processing of children. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 11(5), 366–380.

Scarborough, H. S., & Parker, J. D. (2003). Matthew effects in children with learning disabilities: Development of reading, IQ, and psychosocial problems from grade 2 to grade 8. Annals of Dyslexia, 53(1), 47-71.

Shaywitz, B. A., Holford, T. R., Holahan, J. M., Fletcher, J. M., Stuebing, K. K., Francis, D. J., & Shaywitz, S. E. (1995). A Matthew Effect for IQ but not for reading: Results from a longitudinal study. Reading Research Quarterly, 30(4), 894–906.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed