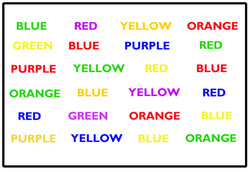

She says that some people are taking my writing on the experiments that have tested predictions of learning styles theories (see here) as implying that teachers ought not to use these theories to inform their practice.

My own learning style is Gangnam

My own learning style is Gangnam The larger issue--the relationship of basic science to practice--is complex enough that I thought it was worth writing a book about it. But I'll describe one important aspect of the problem here.

There are two methods by which one might use learning styles theories to inspire ones practice. The way that scientific evidence bears on these two methods is radically different.

Method 1: Scientific evidence on children's learning is consistent with how I teach.

Teachers inevitably have a theory--implicit or explicit--of how children learn. This theory influences choices teachers make in their practice. If you believe that science provides a good way to develop and update your theory of how children learn, then the harmony between this theory and your practice is one way that you build your own confidence that you're teaching effectively. (It is not, of course, the only source of evidence teachers would consider.)

It would seem, then, that because learning styles theories have no scientific support, we would conclude that practice meant to be consistent with learning styles theories will inevitably be bad practice.

It's not that simple, however. "Inevitably" is too strong. Scientific theory and practice are just not that tightly linked.

It's possible to have effective practices motivated by a theory that lacks scientific support. For example, certain acupuncture treatments were initially motivated by theories entailing chakras--energy fields for which scientific evidence is lacking. Still, some treatments motivated by the theory are known to be effective in pain management.

But happy accidents like acupuncture are going to be much rarer than cases in which the wrong theory leads to practices that are either a waste of time or are actively bad. As long as we're using time-worn medical examples, let's not forget the theory of four humors.

Bottom line for Method 1: learning styles theories are not accurate representations of how children learn. Although they are certainly not guaranteed to lead to bad practice, using them as a guide is more likely to degrade practice than improve it.

Method 2: Learning styles as inspiration for practice, not evidence to justify practice.

In talking with teachers, I think this second method is probably more common. Teachers treat learning styles theories not as sacred truth about how children learn, but as a way to prime the creativity pump, to think about new angles on lesson plans.

Scientific theory is not the only source of inspiration for classroom practice. Any theory (or more generally, anything) can be a source of inspiration.

What's crucial is that the inspirational source bears no evidential status for the practice.

In the case of learning styles a teacher using this method does not say to himself "And I'll do this because then I'm appealing to the learning styles of all my students," even if the this was an idea generated by learning styles. The evidence that this is a good idea comes from professional judgment, or because a respected colleague reported that she found it effective, or whatever.

Bottom line for Method 2: Learning styles theories might serve as an inspiration for practice, but it holds no special status as such; anything can inspire practice.

The danger, of course, lies in confusing these two methods. It would never occur to me that a Disneyland-inspired lesson is a good idea because Disneyland represents how kids think. But that slip-of-the-mind might happen with learning styles theories and indeed, it seems to with some regularity.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed