There are two problems with verbally thrashing people who say something you think lacks scientific support. First, it’s simply a bad tactic. You look like a bully and snob; sure, the flush of self-righteousness is heady, but you’re not informing the other person, although you're pretending to. You’re not even really talking to them, you’re just enjoying yourself.

The second problem caused by the uncritical dismissal of disproven theories is that you might miss new developments. I’ve written about learning styles theories many times and my view of these theories has changed, (see here versus here) notably from excellent experimental work by David Kraemer, Josh Cuevas, and others. If you hear “learning styles” and immediately shout “Nonsense! Ridiculous!” without noticing that someone is providing new data in a well-conducted study, you miss things.

Which brings me to a study published by my colleague at UVa, Vikram Jaswal, about which I tweeted a earlier this week.

The story of facilitated communication has become a staple in psychology methods courses, along with Clever Hans, and it also generated interest in a particular type of unconscious social influence and the methods by which we consciously interpret the reasons for our own behavior. (Which in turn provided Dan Wegner, my colleague at UVa that the time, and a lover of puns, the chance to publish a paper titled Clever Hands.)

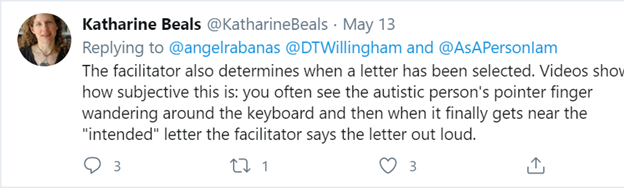

The more recent version of this technique, employed in Jaswal's study, has the assistant holding the letterboard, but not touching the person who’s typing. This removes one way the assistant might be authoring the communication, but not all; the assistant might subtly indicate which letter is to be selected.

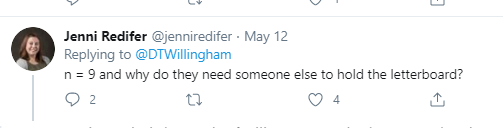

The study I tweeted about examined eye movements and pointing in a small (N=9) group of autistics who regularly use this method. The predictions are straightforward; if you think people are responding to cues, that’s a 26-choice response time task, and RTs in that sort of task would be slow, and people would make a lot of errors. You’d also predict that they would look at the assistant fairly often. If, in contrast, you think that participants are actually typing themselves, you’d expect fluent typing, you’d expect eye movements to lead finger movements without checking what the assistant was doing, and perhaps most interesting, you’d expect that response times would be slow at the start of a new word (for a multiword response) or at the beginning of the second morpheme in a compound word (like “scarecrow”). This effect us observed in touch typists, and are due to motor planning processes.

The authors claimed that the data were consistent with the interpretation that those typing were agentic—at least part of the behavior was self-generated, rather than being fully determined by external cues. It’s the first such demonstration, which helps explain why it was published in a prestigious journal.

The response to my Tweet was a series of Tweets that were highly critical of…lots of things, and were reminiscent of the sort of thing David Weston asked me about regarding learning styles. I’ll provide just a very small sample of them.

These two tweets suggested that the lead author (Jaswal) had an association with some people who do terrible things.

This person wanted the authors to conduct a different experiment.

All of these tweets have one thing in common: they don’t address the study. You can debate whether the researchers should have run a different study, and just how terrible some people who use this method are or aren’t, but there the data sit, waiting to be explained.

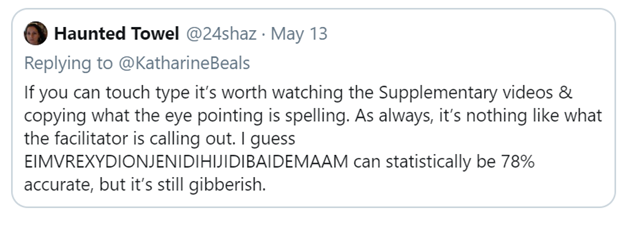

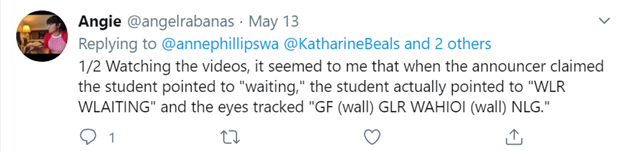

Some critics did try to address issues with the data.

This next bit would be an important criticism, except this person too appears not to have read the methods section, which describes how it was determined which letter the speller pointed to.

I've picked out tweets that addressed methods, but for the most part, people didn’t engage with the actual study to discredit it. They attacked the experimenter and his associates, they broadly said it’s obvious this can’t work, they said the method has been discredited before.

If they really wanted to shoot for the soft spot of this study, they should have gone after things like the calculation of the simulation of the percentage of points to correct letters preceded by a fixation of that letter if fixations had been random—that was used as a baseline for the analysis that supported a key conclusion of the study, and the method the authors used is probably open to debate.

Now, what do I really think of this study? Of course this study should be replicated, and ideally in a different lab. That’s always the case; researchers may have made a mistake, equipment have been flukey, who knows. Equally obviously, the data are consistent with agency, nothing more—it’s not a test of whether a therapeutic technique or a communication method work. It’s also not a test of whether there was absolutely no influence by the assistant holding the board. The authors note that there certainly was…she sometimes finished words or interrupted, sort of the way speakers do. Their claim was that the data can’t be explained by influence alone.

Back to my conversation with David Weston about learning styles. When we feel sure we know something, disconfirming data pose a problem. You have three choices. The first of the three is the worst, and it’s mostly what we saw here; you castigate the study as terrible and obviously stupid but don’t provide any substantive evidence regarding problems with the method, analysis, or interpretation. The second is to engage with the substance of the research and critique it. But that takes a lot of time and expertise. We saw some attempts at such criticism here, and we saw transparent failure to actually read the study, as well as lack of expertise. Which brings me to the third response. You have a feeling the conclusion is probably wrong because it conflicts with a whole lot of other theory and data. But you don’t know the particulars of what’s wrong with this experiment. So you ignore it.

Lest you think I'm suggesting that people just shut up, I'll tell you that I respond in this third way all the time. I see a study that I think doesn't square with a lot of other theory and data and I think "that's probably wrong." And I ignore it. If someone replicates it or if the study becomes a big deal, I'll get worked up, but not before.

It's not bad poker, folks. A hell of a lot of studies don't replicate, as we all know.

I'm guessing the critics of Jaswal's study would say they can't ignore this study because the stakes are so high. It's my perception that there's no little indignation in many of these tweets. As in every education debate I've seen, each side feels that they are motivated by what's best for students whereas the other side is motivated by greed and evil, filtered through stupidity and stubbornness.

Which brings me back to the start of this blog. I suggested that pleasure lies behind the righteous indignation people apply to the learning styles issue. Emotion was at play here. It wasn’t positive emotion in this case, but the outcome was the same. Nobody learned anything, and nobody was convinced.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed