Even before the CCSS, key ideas from some content areas were left to later grades, presumably because students wouldn’t understand them earlier. For example, evolution has usually been taught in high school, even though it’s a foundational idea biology that, if students had under their belts, would likely make learning other concepts easier. The latest standards from Achieve, the National Research Council, and AAAS all take that tack.

It may seem foolish to suggest that students could tackle evolutionary ideas earlier, given that they frequently don’t understand them now. High schoolers usually understand the general idea of adaptation, but they focus on individuals, rather than populations. For example, they think that an individual’s efforts over a lifetime are influential in shaping its fitness, rather than random variation making some animals more fit, and thus more likely to survive and reproduce.

But the history of developmental psychology shows that the age at which children can reach cognitive milestones depends in no small part on the cleverness of the methods used to measure their ability. Perhaps younger students could understand evolution under the right circumstances. A new study (Kelemen et al, 2014) indicates that’s so.

Researchers tested children aged 5 through 8. Kids heard a story about pilosas, fictional animals whose survival was threatened when their food source, insects, started to live below ground in deep, narrow tunnels. Pilosas have trunks which might be wide or narrow. The story went on to explain that in successive generations, trunks became less variable, as pilosas with narrow trunks survived and had young, whereas pilosas with wide trunks could not get enough to eat and did not reproduce.

Researchers tested comprehension of the story and children’s ability to generalize the biological principle to a new case. They were tested immediately and after three months. Each test included ten questions in all (five open, five closed) which probed understanding of different aspects of natural selection such as differential survival, differential reproduction, and the passing on of traits between generations.

7 and 8 year-old children showed good comprehension of the story, with nearly half showing an understanding of the natural selection in one generation and 91% showing at least a partial understanding. Remarkably, 3 months later, this knowledge transferred more or less intact to a story about a new species.

A second experiment replicated the first AND added the idea of trait constancy within an individual; what you’re born with, you retain. This extra detail seemed to help, with still higher percentages of children showing complete understanding and transfer to a new case.

No one would claim that these children have a complete understanding of natural selection. But they got much farther along in their understanding than I think most would have guessed.

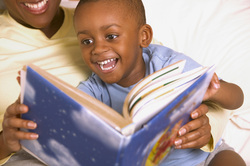

The authors speculate that children did so well because the explanation capitalized “on young children’s drive for coherent explanation, factual knowledge, and interest in trait function, along with their affinity for picture storybooks.”

They further speculate that explaining natural selection at a younger age may have worked out so well because they were not old enough to have developed naïve theories of species change; ideas that would become entrenched and potentially make it more difficult to understand natural selection properly.

The practical implication of this result is obvious; students may be ready to learn concepts of evolution much earlier than most have thought. It also invites the question of whether we do students a disservice if we are too quick to dismiss content as “developmentally inappropriate.”

Reference:

Kelemen, D., Emmons, N. A., Schillaci, R. S., Ganea, P. A., Lillard, A., Rottman, J., & Smith, H. Young (in press). Children Can Be Taught Basic Natural Selection Using A Picture Storybook Intervention. Psychological Science.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed