Just in case you have been away from this planet for the last few months, ‘Fidget Spinners’ are the latest toy sensation. Some have suggested (without any evidence) that this new gadget is "perfect for children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, autism, anxiety." Although there's no evidence for that, kids love them, which has prompted a flurry of interest in possible educational applications (see here), and educators have come up with creative ways of integrating spinners into educational activities (when they are not banning them, see here).

One such idea was the subject of a tweet by Dan on June 14th. The idea is simple: students use the spinner as a timer and try to solve as many math fact problems as possible while it is spinning.

Negative responses fell into two categories. One suggested that timed practice would lead to math anxiety. The other suggested that this kind of practice might legitimize the much maligned ‘drill and kill’ approach to teaching math.

If a teacher doesn’t like an activity, that’s obviously reason enough not to use it as far as we’re concerned—we’re not in the business of advocating for particular classroom work. But we can point to the research literature bearing on the two common concerns, and based on this research, we don’t think they have merit.

Regarding anxiety: This issue has been raised most prominently by Professor Jo Boaler of Stanford University. For example, she argued in a recent blog that “…timed tests are a major cause of this debilitating, often lifelong condition [referring to math anxiety].”

First, let’s note that the fidget spinner worksheet offers timed practice, not timed assessment, which Boaler mentions. It seems to us that in a zero-stakes situation like a worksheet, the main agent of anxiety would be social comparison, an issue that teachers have plenty of experience handling.

Second, when it comes to timed assessments, the evidence for an anxiety link is still lacking. Boaler cites Ramirez et al (2013) in her blog. This article examined the relationship between working memory and math anxiety and showed, perhaps counterintuitively, that math anxiety impacts students with high working memory more than it does those with relatively lower working memory capacity. The authors argue that because math anxiety affects working memory, through intrusive thoughts and ruminations (“I can’t do this”, “I am terrible at math”), that students who typically use working-memory-demanding strategies are hit the hardest. These data say nothing about speeded math practice--the measure of math achievement used by Ramirez et al was untimed.

In a review of Boaler’s book, Mathematical Mindset , Victoria Simms (@DrVicSimms) writes “…she discusses a purported causal connection between drill practice and long-term mathematical anxiety, a claim for which she provides no evidence, beyond a reference to ‘Boaler (2014c)’ (p. 38). After due investigation it appears that this reference is an online article which repeats the same claim, this time referencing ‘Boaler (2014)’, an article which does not appear in the reference list, or on Boaler’s website.”

Again, it seems obvious to us that if a teacher feels that this sort of activity would make her students anxious, she won’t use it. But it’s not accurate to claim that research shows that this sort of activity generally makes students anxious.

What of the second concern, that students should focus on developing a conceptual understanding of math rather than being able to recall math facts speedily?

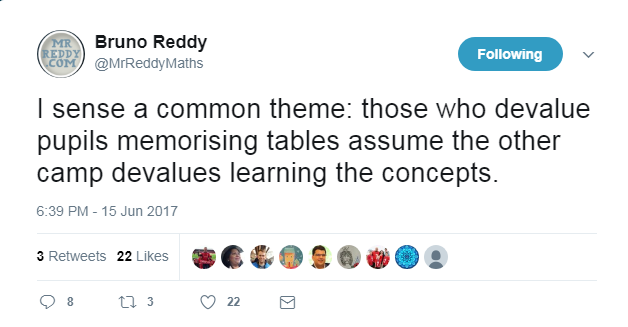

Arguments for speeded recall of math facts are not arguments against building students' conceptual understanding of mathematics. As @MrReddyMath put it:

It was also the conclusion of Professor Bethany Rittle-Johnson, a developmental psychologist at Vanderbilt who has extensively researched the relationship between procedures and concepts in math learning. When asked about the debate regarding memorizing math facts vs. developing conceptual understanding in a 2016 interview she said “Actually, I think it's a silly argument because the evidence is pretty clear that children really need to do both things. Understanding is super-important, but understanding relies on knowing enough that you can understand it. If you have to spend all your time figuring out what two plus three is, then you can't notice relationships between number pairs, [for example].” Practicing math facts should be one of the methods used to help students build solid foundations to scaffold their learning of mathematics.

Fine, but why, you might ask, apply the pressure of timing practice? Does speed matter?

It does. When working a complex problem you not only want to pull simple math facts from memory, you want to do so quickly, so that the other work can proceed apace. Indeed, adults with stronger higher-level math achievement retrieve math facts faster (Hecht, 1999).

And speed matters not just in using math facts but in learning them. Methe et al (2012) conducted a meta-analysis of interventions for basic math in single-case research and reported “we found interventions involving practice under speeded conditions and a carefully controlled instructional sequence produced the strongest effects,” echoing results from Powell et al (2009) who reported that timed practice (vs. untimed) was crucial to an intervention for struggling 3rd-graders to learn math facts, and Fuchs et al. (2013) reporting similar results for 1st graders..

It is clear, as is the case with any learning, that such speeded practice of math facts must be adaptive and appropriate for the level of the learning, and should be scaled gradually. And like everything else in a classroom, it will ideally be engaging. That’s challenging when you’re trying to develop automaticity, because it implies a certain amount of repetition. That’s why we liked the fidget spinner idea; it’s a little twist on a familiar task. It won’t be to every teacher’s taste, but we can say that there is no evidence it will prompt the problems that some feared.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed