Most colleges and universities have programs meant to help students with the process of transitioning, and they often focus on practical skills like choosing classes and study strategies on the assumption that navigating academic life is a significant part of the problem.

In the last few years researchers have focused on a quite different approach: offering students a "lay theory" of the college experience. A lay theory is a set of beliefs that are used to interpret one's experiences. In the case of college, two beliefs have been flagged as especially important: that the transition to college inevitably involves setbacks, and that these setbacks are temporary.

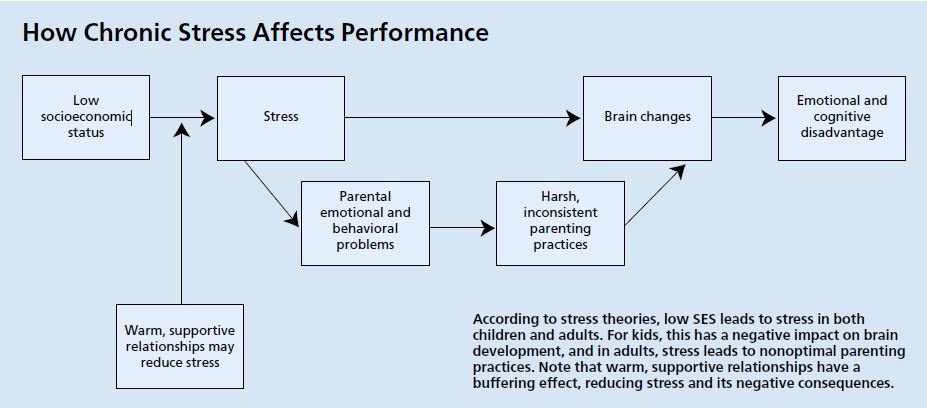

College always includes disappointments, both academic and social. A student fails a test, or a callous professor tells them that their writing is beyond hope. (My freshman year of college an English professor wrote this as the entire comment on my exam essay: "No. D" Students get lonely, and have trouble making friends. For students who grew up in families where it was always assumed that they would attend college, such disappointments are dispiriting, but not threatening. The student may even wonder if he or she belongs in college, but that doubt likely doesn't last. For a student who did not grow up in an environment where it was taken for granted that they would graduate college that doubt may persist. They may think that they are not smart enough to succeed, that they are "not college material," or that their cultural background is not compatible with college.

Researchers have sought ways to instill a lay theory of college that would change that interpretation, focusing on two ideas: setbacks in college are common (and therefore should not be taken as a sign that you don't belong) and setbacks are temporary (so things will get better).

Researchers have had some success with this intervention in smaller experiments (Stephens et al, 2014; Walton & Cohen, 2011. Now a new study (Yeager et al, 2016) suggests that a simple, inexpensive intervention works at scale.

Before they matriculated at college, students participated in an activity taking just 30 minutes, administered over the Internet. They were told that it was to help them think about the transition to college, and that they would have the chance to share their experiences, perhaps helping future students.

There were three experimental conditions. The social belonging condition provided information showing that feeling out of place is common in the transition to college, but most students do make friends and succeed academically. The growth mindset condition provided information showing that intelligence is malleable, and that student can succeed with effort, coupled with effective strategies. The third condition combined both strategies. In each case, students were asked to write an essay about how the information they read might apply to them, as a way of cementing the information in memory, and to help them imagine making it applicable to their own experience.

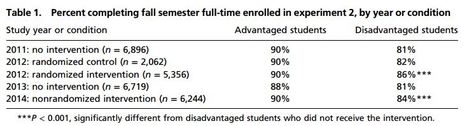

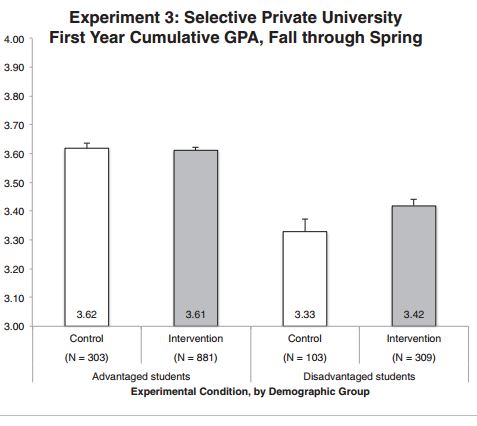

One experiment targeted the entering class of a large public university. As shown in the table below, the intervention improved retention. All three of the intervention conditions were equally effective.

Two things are noteworthy about this experiment. First, the reduction in the achievement gap is quite sizable, on the order of 30-40%. Second, this intervention was remarkably brief, and remarkably inexpensive. Obviously this work needs to be replicated and the interventions fine-tuned. (The growth mindset intervention didn't really work in Experiment 1.) But if this finding holds up, it must be counted as a huge success for social scientists, and for David Yeager and Greg Walton in particular.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed