Do children learn to read by translating letters into sound, or by perceiving the spelling of the word? The answer has an indirect bearing on teaching; it would presumably be best to instruct kids in a way consonant with how most perform the task. The last fifteen years has seen an increasing consensus among researchers: children initially learn via the letter-sound translation mechanism. As they gain reading practice, they acquire the spelling mechanism as well, although the letter-sound translation method continues to make a contribution to reading. Now a new study of 284 French children in grades 1 through 5 offers support to this model (Ziegler et al, 2014).

From the child’s perspective, the experimental task was simple. They sat before a computer screen. An asterisk appeared at the center for one second, and then a string of letters replaced the asterisk (I’ll call this the “response letter string.”) Children were to push one button if the response letter string formed a word, and another if it did not.

What the kids were not told was that another letter string actually appeared between the asterisk’s disappearance and the appearance of the response letter string. This letter string (called the prime) appeared for just .07 seconds, so the children didn’t consciously see it—if anything, they might have thought the screen flickered.

Even though you’re unaware of it, the prime can influence your response. If the prime is “MOP” and then the response letter string is also “MOP,” you’re faster to verify that “MOP” is indeed a word, compared to how fast you respond if the prime were a non-matching word, say, “DOG.” Even though you were unaware of the prime, you read it, and so you’re a bit faster to read it a second time.

But what if the prime were “MAWP?” Would you still be faster to verify that “MOP?” is a word when it appears? If you think that people read via letter-sound translation, the answer ought to be yes. When “MAWP” appears, you read it and generate the right sound, and if sound is the basis of reading, you should get the advantage when “MOP” appears.

Using a comparable method, the researchers tested whether kids read via spelling. They used a prime with nearly the same spelling as the response letter string: for example “TALBE” followed by “TABLE.” Other work has shown the readers are pretty resistant to spelling errors like this one, where letters are off by just one position (McCusker et al, 1981). So if you’re using the spelling of a word to identify it, we can expect that you’ll be faster to verify that “TABLE” is a word if the prime was “TALBE,” compared to a prime like “CAIRH.”

So take a moment and guess. Do first graders read mostly by sound or by spelling? How about fifth graders?

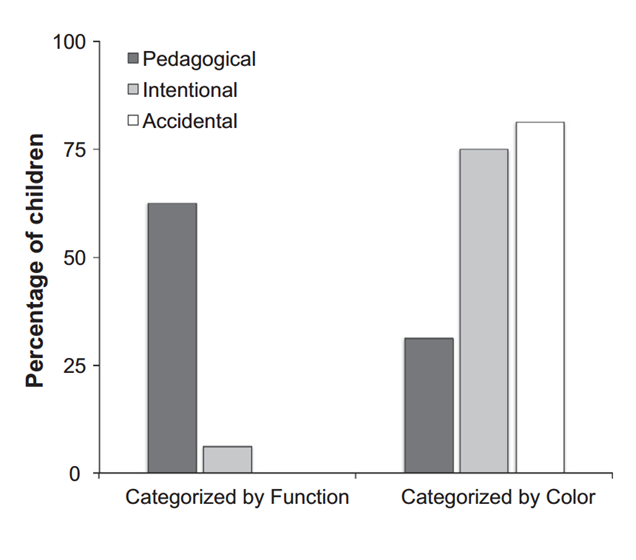

The data indicated that first graders read by sound. With each successive year, kids showed more and more evidence of using the spelling of words in their reading. BUT there was no diminution of the influence of sound. Experienced readers use both the sound and the spelling mechanisms.

This result fits with the following view of reading: most kids will learn to read by learning to sound out words. With practice over the course months and years, they develop an increasing number (and increasingly robust) mental representations that allow them to identify words by their appearance, i.e., by their spelling. These representations form as a consequence of reading practice and don’t require any special instruction. This general view accords with other behavioral data showing that methods of reading instruction that emphasize phonics have an edge over other methods.

References:

McCusker, L. X., Gough, P. B. & Bias, R. G. (1981). Word recognition inside out and outside in. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 7, 538-551.

Ziegler, J. C., Bertrand, D., Lété, B., & Grainger, J. (2014). Orthographic and phonological contributions to reading development: Tracking developmental trajectories using masked priming. Developmental Psychology, 50, 1026-1036.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed