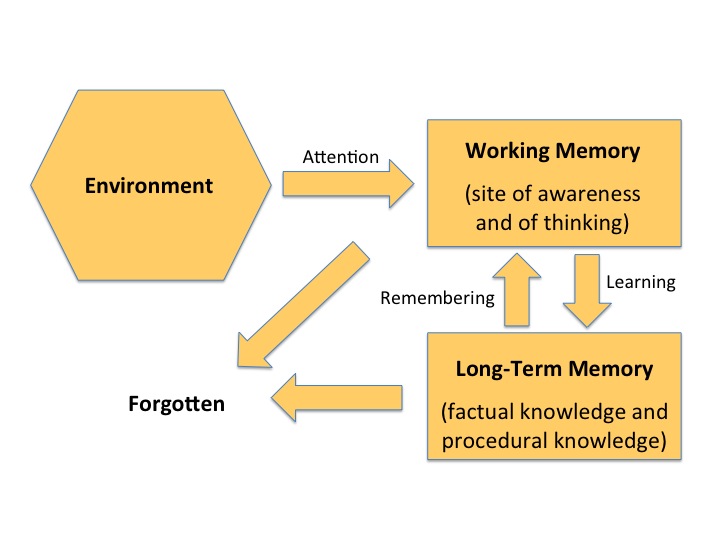

We use two strategies to avoid thinking. If the situation seems similar to one we’ve seen before, we rely on memory and do whatever we did last time. (Retrieving from memory incurs little cognitive cost.) My late colleague, Dan Wegner, had one dish he would order for lunch at each restaurant we frequented. He explained to me, “That way I don’t have to think.”

If the situation is unfamiliar memory won’t work, but you can often get away with heuristics—quick, cognitively inexpensive processing routines that provide an answer, often a good one. One heuristic would be association—produce an answer that is associated in memory with whatever seems to be the key term in the problem.

A classic problem to measure miserly thinking is this:

A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost? cents.

The “not really thinking about it” answer is “10 cents.” You see the word “more,” figure the problem calls for subtraction, perform that operation for the two numbers in the problem, boom, 10 cents. But you don’t check your work.

The last twenty-five years has brought a new strategy: find the answer on the internet. (For the lazy, here you go.) And in the last five, smartphones have become inexpensive enough to deeply penetrate the consumer market--64% of US adults own one.

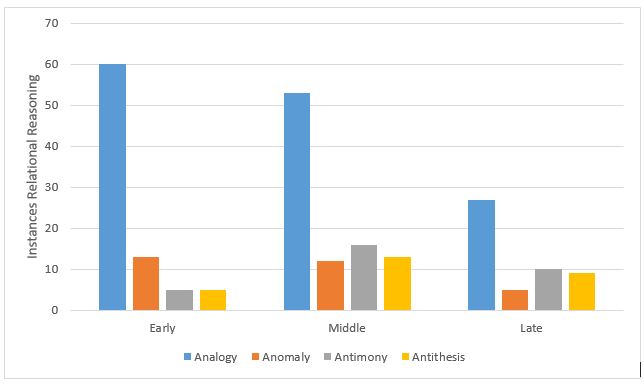

Researchers at University of Waterloo conducted three studies examining the association between self-reported smartphone use and performance on questions like the ball-and-bat problem. They separated respondents into low- medium- and high-smartphone usage groups. They found no difference between the low and medium groups, but the high usage group was less accurate on the analytic problems.

Researchers found that the effect held for total number of minutes subjects reported using their smartphones, and for search engine use, but not number of minutes spent on entertainment sites (YouTube, Reddit) or social media sites (Facebook, Snapchat). So the researchers were able to confirm a somewhat more fine-grained version of their hypothesis that people who are more cognitively miserly are more likely to search information out on their smartphone.

Researchers also reported a negative correlation between smartphone use and cognitive ability (as measured by brief numeracy and verbal intelligence tests), an association reported in previous research. The reason is not clear. It may be that low-cognitive-ability people seek information—look up a word meaning, calculate a tip—that high-ability people have in their heads.

The authors rightly point out that their study should be thought of as just the start of what will have to be a much broader research program (or set of programs) examining how people interact with technology that can be provide cognitive support, and that is nearly always available to us. The idea of “external memory”—that we know information useful to us is available, even though it is stored in others and in recorded sources—is very old. William James discussed it Principles of Psychology over 100 years ago. Dan Wegner proposed a particular conceptualization of this idea in 1985.

New technology has made external memory complicated and the need for understanding it more urgent. Many of us spend a lot of time with our smartphones—is it making us more cognitively miserly, or are misers simply taking advantage of a new opportunity? What are the costs and benefits of either change?

The ideal design would be to examine short- and long-term changes in individual habits when people first gain access to a smartphone, but the opportunity to conduct such a study is fast disappearing.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed