The authors note that video gaming has been linked to obesity, aggressiveness, and antisocial behavior, but there is a burgeoning literature showing some cognitive benefits accrue from gaming. Even though the data on these benefits is not 100% consistent (as I noted here) I'm with Bavelier & Davidson in their general orientation: so many people spend so much time gaming, we would be fools not to consider ways that games might be turned to purposes of personal and societal benefit.

Could games help to make people smarter, or more empathic, or more cooperative?

The authors suggest three developments are necessary.

- Game designers and neuroscientists must collaborate to determine which game components "foster brain plasticity." (I believe they really mean "changes behavior.")

- Neuroscientists ought to collaborate more closely with game designers. Presumably, the first step will not get off the ground if this doesn't happen.

- There needs to translational game research, and a path to market. We expect that some research advances (and clinical trials) of the positive effects of gaming will be made in academic circles. This work must get to market if it is to have an impact, and there is not a blazed trial by which this travel can take place.

This is all fine, as far as it goes, but it ignores two glaring problems, both subsets of their first point.

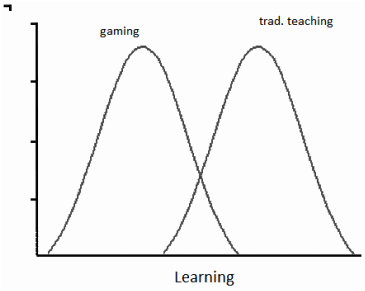

We have to bear in mind that Bavelier & Davidson's enthusiasm for the impact of gaming is coming from experiments with people who already liked gaming; you compare gamers with non-gamers and find some cognitive edge for the former. Getting people to play games is no easy matter, because designing good games is hard.

This idea of harnessing interest in gaming for personal benefit is old stuff in education. Researchers have been at it for twenty years, and one of the key lessons they've learned is that it's hard build a game that students really like and from which they also learn (as I've noted in reviews here and here.)

Second, Bavelier & Davidson are also a bit too quick to assume that measured improvements to basic cognitive processes will transfer to more complex processes. They cite a study in which playing a game improved mental rotation performance. Then they point out that mental rotation is important in fields like navigation and research chemistry.

But one of the great puzzles (and frustrations) of attempts to improve working memory has been the lack of transfer; even when working memory is improved by training, you don't see a corresponding improvement in tasks that are highly correlated with working memory (e.g., reasoning).

In sum, I'm with Bavelier & Davidson in that I think this line of research is well worth pursuing. But I'm less sanguine than they are, because I think their point #1--getting the games to work--is going to be a lot tougher than they seem to anticipate.

Bavelier, D, & Davidson, R. J. (2013). Brain training: Games to do you good. Nature, 494, 425-426.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed