Students arrive at college with different levels of preparation to handle these responsibilities. Unsurprisingly, family background makes a difference. Students who are the first in their families to attend college (first-generation students) earn lower grades and drop out at higher rates than students with at least one parent who attended college (continuing-generation students), controlling for high school GPA (Pascarella et al 2004). (Otherwise-successful charter schools are struggling with this social-class achievement gap.)

What fuels the gap? Partly the access that continuing-generation students have to advice from parents on how best to navigate college—access that first-generation students obviously lack. Colleges try to make up for this difference by offering programs to aid first-generation students; programs that offer advice on how to select a major, how to manage one’s time, and so on.

But first-generation students don’t take colleges up on their offers of help. They are less likely to take advantage of college services than continuing-generation students.

That may be because first-generation students are unsure whether or not they really belong at college, whether they can succeed.

Taking a cue from similar studies examining race (e.g., Walton & Cohen, 2011) a new study Stephens et al, in press) sought to change how freshmen students thought about their family backgrounds by exposing them to stories of successful upper-class students, who described how their family backgrounds could be a source of challenges and of strength.

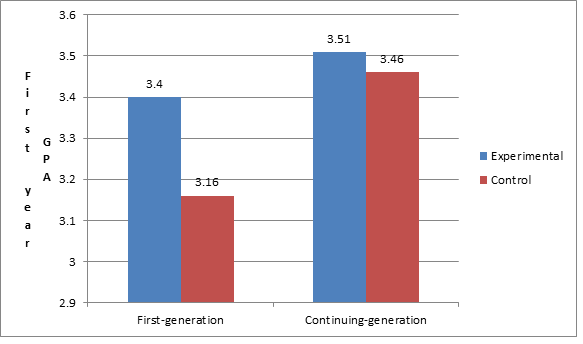

First-generation (N=66) and continuing-generation (N=81) freshman students attended a panel discussion by college seniors on college adjustment.

For half of the freshman, the panelists’ answers were linked to their family backgrounds. For example, a first-generation panelist pointed out that his parents couldn’t provide much advice about selecting classes, so he learned that he had to rely on his advisor more than other students. The continuing-generation students highlighted that they faced challenges as well: a panelist mentioned that she had attended a small private school that offered a lot of one-on-one attention, and that she felt lost in large lecture classes.

The other half of the freshman served as the control condition: they attended a different panel discussion in which challenges of college life and how to address them were discussed, but the answers were not directly linked to family background.

At the end of the year, this brief, one-time intervention had significantly reduced the social-class gap, as measured by cumulative GPA.

Anytime you hear about a one-hour intervention that has such a profound and long-lasting effect, it’s natural to be suspicious. Certainly, we’d like to see this effect replicated, but there is at least a plausible explanation for the profound effect; the intervention provides a new way for students to think about difficulties. Instead of evidence that they don’t really belong at college, set-backs become a normal part of college life, and one that can be addressed.

References

Pascarella, E., Pierson, C., Wolniak, G., & Terenzini, P. (2004). First-generation college students: Additional evidence on college experiences and outcomes. Journal of Higher Education, 75, 249–284.

Stephens, N. M., Hamedani, M. G., & Destin, M. (in press). Closing the Social-Class Achievement Gap A Difference-Education Intervention Improves First-Generation Students’ Academic Performance and All Students’ College Transition. Psychological science.

Walton, G. M., & Cohen, G. L. A brief social-belonging intervention improves academic and health outcomes of minority students. Science, 331, 1447-1451.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed