It concerns the magnocellular theory of dyslexia (Stein, 2001). According to this theory, many varieties of reading disability have, at their core, a problem in the functioning of the magnocellular layer of the lateral geniculate nucleus of the thalamus. This layer of cells is known to be important in the processing of rapid motion, and people with developmental dyslexia are impaired on certain visual tasks entailing motion, such detecting coherent motion amongst a subset of randomly moving dots, or discriminating speeds of objects.

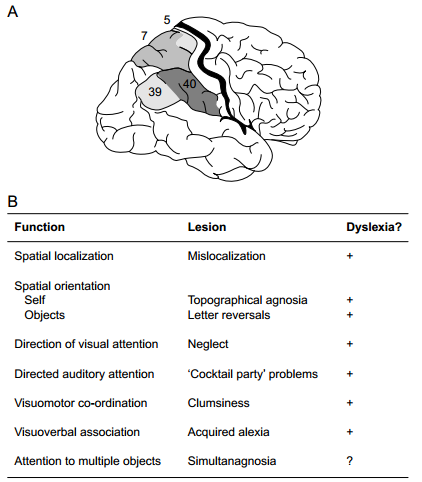

The most widely accepted theory of reading disability points to a problem in phonological awareness—hearing individual speech sounds. The magnocellular theory emphasizes that phonological processing does not explain all of the data. There are visual problems in dyslexia as well. Proponents point to problems like letter transpositions and word substitutions while reading, and to visuo-motor coordination problems (Stein & Walsh, 1997; see Figure below) although the pervasiveness of these symptoms are not uncontested.

It’s certainly an interesting hypothesis, but the data have been correlational. Maybe learning to read somehow steps up magnocellular function. That’s where Eden and her team come in.

They compared kids with dyslexia to kids with typical reading development and found (as others have), reduced processing in motion detection cortical area V5. But then they compared kids with dyslexia to kids who were matched for reading achievement (and were therefore younger). Now there were no V5 differences between groups. These data are inconsistent with the idea that kids with dyslexia have an impaired magnocellular system. They are consistent with the idea that reading improves magnocellular function. (Why? A reasonable guess would be that reading requires rapid shifts of visual attention).

In a second experiment, the researchers trained kids with dyslexia with a standard treatment protocol that focused on phonological awareness. V5 activity—which, again, is a cortical area concerned with motion processing--increased after the training! This result too, is consistent with the interpretation that reading prompts changes in magnocellular function.

These are pretty compelling data indicating that reading disability is not caused by a congenital problem in magnocellular functioning. We see differences in motion detection between kids with and without dyslexia because reading improves the system’s functioning.

The finding is interesting enough on its own, but I also want to point out that it’s a great example of how neuroscientific data can inform problems of interest to educators. About a year ago I wrote a series of blogs about techniques to solve this difficult problem.

Eden’s group used a technique where brain activation is basically used as a dependent measure. Based on prior findings, researchers confidently interpreted V5 activity as a proxy for cognitive activity for motion processing. Indistinguishable V5 activity (compared to reading-matched controls) was interpreted as a normally operating system to detect motion. And therefore, not the cause of reading disability.

I’m going out of my way to point out this success because I’ve so often said in the past that neuroscience applied to education has mostly been empty speculation, or the coopting of behavioral science with neuro-window-dressing.

And I don’t want educators to start abbreviating “brain science” as BS.

References:

Cornelissen, P., Richardson, A., Mason, A., Fowler, S., and Stein, J. (1995). Contrast sensitivity and coherent motion detection measured at photopic luminance levels in dyslexics and controls. Vision Research, 35, 1483–1494.

Demb, J.B., Boynton, G.M., and Heeger, D.J. (1997). Brain activity in visual cortex predicts individual differences in reading performance. PNAS, 94, 13363–13366.

Livingstone, M.S., Rosen, G.D., Drislane, F.W., and Galaburda, A.M. (1991). Physiological and anatomical evidence for a magnocellular defect in develop-mental dyslexia. PNAS, 88, 7943–7947

Stein, J. (2001). The magnocellular theory of developmental dyslexia. Dyslexia, 7, 12-36.

Stein, J. & Walsh, V. (1997). To see but not to read: The magnocellular theory of dyslexia. Trends in Neurosciences, 20, 147-152.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed