When someone behaves immorally, a psychologist would typically say that the individual has not internalized the moral norm; that is, she may profess that an action is morally wrong, but she has not really taken that information to heart.

How can a parent or teacher encourage such internalization?

Attribution theories have been quite influential in how psychologists think about this matter. These theories hold that a parent should NOT ensure moral behavior through the use of harsh or punitive measures.

Doing so will gain compliance because the child will want to avoid punishment, but the child will not internalize the norm. He will attribute his "good" behavior not to his own belief in the moral precept, but to the desire to avoid punishment.

That theory would predict, then, that once the threat of punishment is removed, these children will engage in the forbidden behavior. That prediction is born out in research.

But another prediction of the theory is wrong. If children have not internalized the moral precept, they should feel no shame if they break the rule. But they do feel ashamed.

Sana Sheik and Ronnie Janoff-Bulman (2013) sought to resolve this paradox.

Their hypothesis: punitive parenting on moral matters does lead children to internalize the moral precept (hence the shame). But it also paradoxically makes children less well equipped to resist temptation (hence the tendency to engage in the immoral behavior).

Why would it be harder to resist temptation? Well, imagine that I say to you "Hey, it would probably be better if you didn't think about white bears." The idea of a white bear would flash in your mind, but you'd soon think about something else.

That's the theory. The experimental data seem to support it, although the logic is a little convoluted.

First, subjects were asked to fill out a questionnaire about discipline used by their parents. Responses were used to judge the extent to which parents were punitive about moral matters. (This use of questionnaires is common in this literature.)

Second, experimenters asked subjects to write out moral precepts; some subjects wrote about positive precepts (things that you should do) or proscriptive ones (things you should not do). They did this to prime subjects, that is, to get them thinking about these moral issues.

They varied the type of precept (positive or proscriptive) because harsh parental control is virtually always directed at moral proscriptions.

Here's the idea. subjects who had first been prompted to think about moral proscriptions would be thinking about moral proscriptions when they saw the paintings, but they were told NOT to use those thoughts in describing the paintings. Inhibiting those thoughts would presumably "cost" them--their resources for regulating attention would be somewhat depleted. And that should be especially true for students whose parents were punitive about moral matters because such issues are hyper-charged for them.

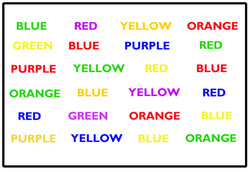

How could you show that their attentional resources were depleted from the struggle to not think about moral proscriptions?

And, as predicted, subjects whose parents were punitive were worse on the STROOP task than subjects whose parents were not.

But maybe kids with punitive parents are bad at the STROOP for other reasons. Maybe these just happen to be kids who lack attentional resources. In fact, maybe that's why they often got in trouble, and that's why their parents had to be kind of hard on them.

That's why the experimenters also included a condition where subjects were asked to think about positive moral precepts. Without that prime, everyone should find it easier NOT to think about proscriptive morality. And indeed, subjects whose parents were punitive don't have a particular problem with the STROOP in this condition.

As I promised, the chain of logic supporting the theory is a bit convoluted. Still, the basic account seem plausible.

If further data support the theory, the upshot for parents and teachers would be that harsh responses to moral transgressions won't work. They leave subjects feeling ashamed when they transgress, but paradoxically they make is harder to resist the temptation to transgress.

Shikh, S. & Janoff0Bulman, R. (2013). Paradoxical consequences of prohibitions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Advance online publication: doi: 10.1037/a0032278

RSS Feed

RSS Feed