("Retrieval practice" is less catchy than the initial name--testing effect. It was renamed both to emphasize that it doesn't matter whether you try to remember for the sake of a test or some other reason and because "testing effect" led some observers to throw up their hands and say "do we really need more tests?")

Now researchers (Szpunar, Khan, & Schacter, 2013) have reported testing as a potentially powerful ally in online learning. College students frequently report difficulty in maintaining attention during lectures, and that problem seems to be exacerbated when the lecture occurs on video.

In this experiment subjects were asked to learn from a 21 minute video lecture on statistics. They were also told that the lecture would be divided in 4 parts, separated by a break. During the break they would perform math problems for a minute, and then would either do more math problems for two more minutes ("untested group"), they would be quizzed for two minutes on the material they had just learned ("tested group"), or they would review by seeing questions with the answers provided ("restudy group.")

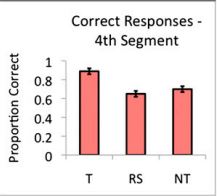

Subjects were told that whether or not they were quizzed would be randomly determined for each segment; in fact, the same thing happened for an individual subject after each segment except that each was tested after the fourth segment.

So note that all subjects had reason to think that they might be tested at any time.

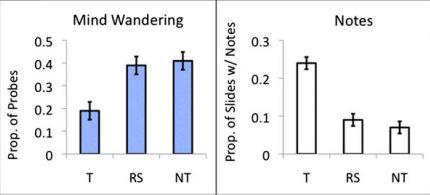

There were a few interesting findings. First, tested students took more notes than other students, and reported that their minds wandered less during the lecture.

We shouldn't get out in front of this result. This was just a 21 minute lecture, and it's possible that the benefit to attention of testing will wash out under conditions that more closely resemble an on-line course (i.e., longer lectures delivered a few time each week.) Still, it's a promising start of an answer to a difficult problem.

References

Agarwal, P. K., Bain, P. M., & Chamberlain, R. W. (2012). The value of applied research: Retrieval practice improves classroom learning and recommendations from a teacher, a principal, and a scientist. Educational Psychology Review, 24, 437-448.

McDaniel, M. A., Thomas, R. C., Agarwal, P. K., McDermott, K. B., & Roediger, H. L. (2013). Quizzing in middle-school science: Successful transfer performance on classroom exams. Applied Cognitive Psychology. Published online Feb. 25

Rohrer, D., Taylor, K., & Sholar, B. (2010). Tests enhance the transfer of learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 36, 233-239.

Szpunar, K. K., Khan, N. &, & Schacter, D. L. (2013). Interpolated memory tests reduce mind wandering and improve learning of online lectures. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, published online April 1, 2013 doi:10.1073/pnas.122176411

RSS Feed

RSS Feed