It might make sense cognitively, but the literature shows that such a practice leads to bad outcomes for the kids in lower tracks. Those classes tend to have less demanding curricula and and lower expectations for achievement (e.g., Brunello & Checchi, 2007).

Further, assignment to tracks is often biased by race or social class (e.g., Maaz et al., 2007).

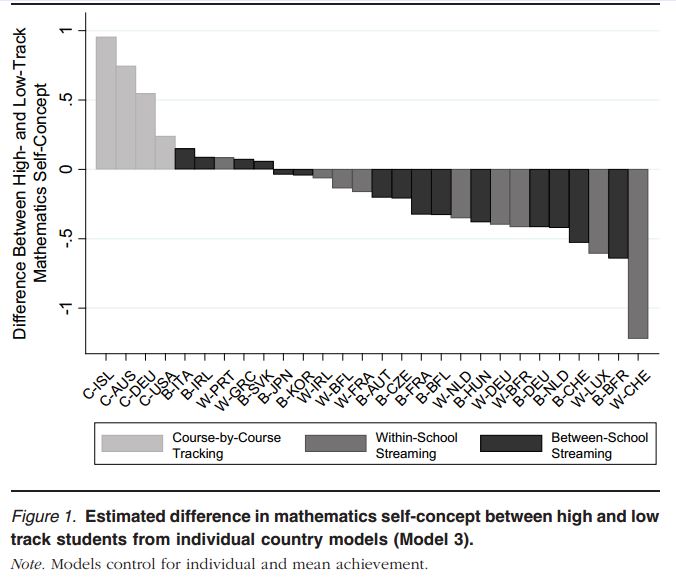

What tracking does to students self-perceptions has been less clear. A new international study (Chmielewski et al., 2013) examined data from the 2003 PISA data set to examine the association of different types of tracking and student self-perceptions of mathematics self-concept.

The authors compared systems with

- Between school streaming: in which students with different levels of achievement are sent to different schools.

- Within school streaming: in which students with different levels of achievement are put in different sequences of courses for all subjects.

- Course-by-course tracking: in which students are assigned to more or less advanced courses within a school, depending on their achievement within a particular subject.

Controlling for individual achievement and the average achievement of the track or stream, the researchers found that course tracking is associated with worse self-perceptions among low-achieving students, but streaming is associated with better self-perceptions.

This figure shows the difference between the self perceptions of higher and lower achieving students in individual countries, sorted by the type of tracking system.

But why is there self-concept higher than higher-achieving students? This effect may be comparable to a more general phenomenon that people are poorer judges of their competence for tasks that they perform poorly. If you're not very good, you're not good enough to realize what you lack.

The authors do not suggest that between school steaming is the way to go (since it's associated with higher confidence). They note that the association is just the reverse of that seen in achievement: kids who stream between schools seem to take the biggest hit to achievement.

References

Brunello, G., & Checchi, D. (2007). Does school tracking affect equality of opportunity? New international evidence. Economic Policy, 22, 781–861.

Chmielewski, A. K., Dumont, H. Trautwein, U. (2013). Tracking effects depend on tracking type: An international comparison of students' mathematics self-concept. American Educatioal Research Journal, 50, 925-957.

Maaz, K., Trautwein, U., Ludtke, O., & Baumert, J. (2008). Educational transitions and differential learning environments: How explicit between-school tracking contributes to social inequality in educational outcomes. Child Developmental Perspectives, 2, 99–106.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed