The groundbreaking work of Hart & Risley (1995; replicated by others, e.g. Huttenlocher et al, 2010) showed that socio-economic status of the parents is correlated with vast differences in the amount and complexity of language that children hear at home.

But what aspect of this speech is important? Does speech need to be directed to children? Perhaps all that’s needed is for children to be in the presence of this more complex language. After all, we know that children do not learn language via instruction; they learn it by observation.

Three studies published in the last couple of years build a convincing case that parents should, indeed, talk to their children. Talking in the presence of their children (but to others) does not confer the same vocabulary benefit.

In the most recent study (Weisleder & Fernald, 2013), experimenters tested 29 Spanish-learning infants at age 19 months. The children wore a small device that made an audio recording of all speech to which the child was exposed. The audio recordings were analyzed by software meant to differentiate speech directed toward the child versus speech audible to the child, but directed to others. A subset of recordings was coded by human observers to ensure the accuracy of the software.

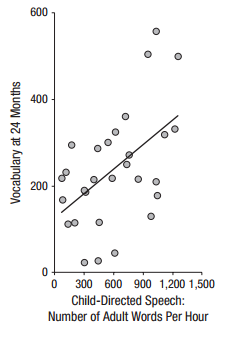

Recordings of a full day’s speech were analyzed and the results showed a huge range in child-directed speech; caregivers in one family spoke over 12,000 words to the child whereas in another family that figure was just 670 words. The amount of child-directed speech as not significantly correlated (r = .17) with the amount of overheard speech.

At 24 months the productive vocabulary of the children was measured by asking the parents to judge words that they believed their child understood and words that their child used.

Of greatest interest, the amount of child-directed speech at 19 months was correlated (r = .57) with vocabulary at 24 months. The amount of overheard speech at 19 months was not (r = .25).

Why must speech be directed to the child?

Weisleder & Fernald administered another task at 19 months meant to measure word processing efficiency. They speculated that the effect of child-directed speech on vocabulary was mediated through efficiency—something like, for example, the speed and accuracy with which the particular phonemes of the child’s language are processed.

This doesn’t fully explain the difference between child-directed and overheard speech. The obvious hypothesis is that other cues (e.g. eye gaze direction) prompt greater attention to speech that is child-directed, and that attention is necessary to build efficiency.

More details will have to await further research. For now, we can say with greater confidence “talk to your children” not just “talk in the presence of your children.”

References

Hart, B. M., & Risley, T. R. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

Huttenlocher, J., Waterfall, H., Vasilyeva, M., Vevea, J., & Hedges, L. V. (2010). Sources of variability in children’s language growth. Cognitive Psychology, 61, 343–365.

Shneidman, L. A., Arroyo, M. E., Levine, S., & Goldin-Meadow, S. (2013). What counts as effective input for word learning? Journal of Child Language, 40, 672–686.

Shneidman, L. A., & Goldin-Meadow, S. (2012). Language input and acquisition in a Mayan village: How important is directed speech? Developmental Science, 15, 659–673.

Weisleder, A. & Fernald, A. (2013). Talking to children matters: Early language experience strengthens processing and builds vocabulary. Psychological Science, DOI: 10.1177/0956797613488145

RSS Feed

RSS Feed