It’s important to keep this perspective in mind as we continue to process the horrific school shooting in Parkland, Florida. Just as my friend knew that losing your spouse is not resolved in six months, we might guess that the trauma associated with attending a high school where murder took place would have long term consequences.

In fact, Louis-Philippe Beland and Dongwoo Kim have examined the educational consequences for survivors. Using the Report on School Associated Violent Deaths from the National School Safety Center, they identified 104 shootings categorized as homicidal and 53 as suicidal. (Shootings took place on the property of a public or private US school, or while a person was attending or on their way to or from a school-sponsored event.)

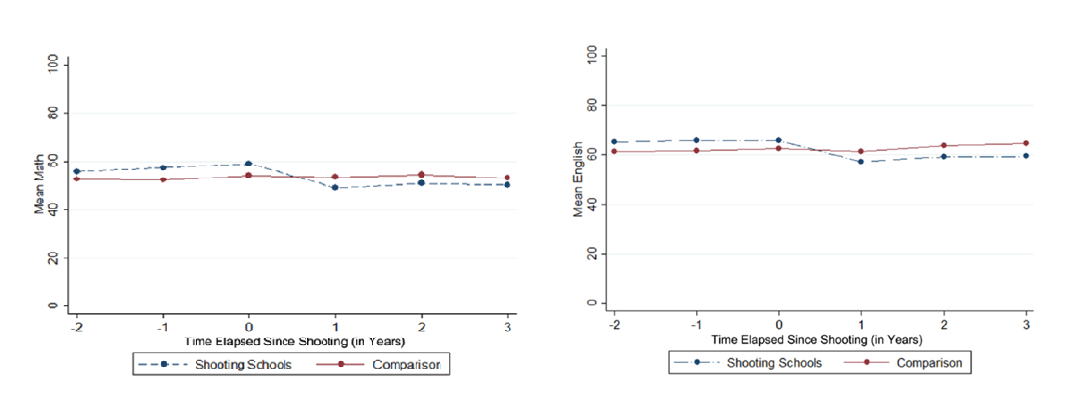

School performance data were obtained from each state’s Department of Education website. The researchers used other schools in the same district for comparisons, on the reasoning they would be roughly matched for demographics. (I wonder about the soundness of this assumption.) The researchers examined three main outcomes.

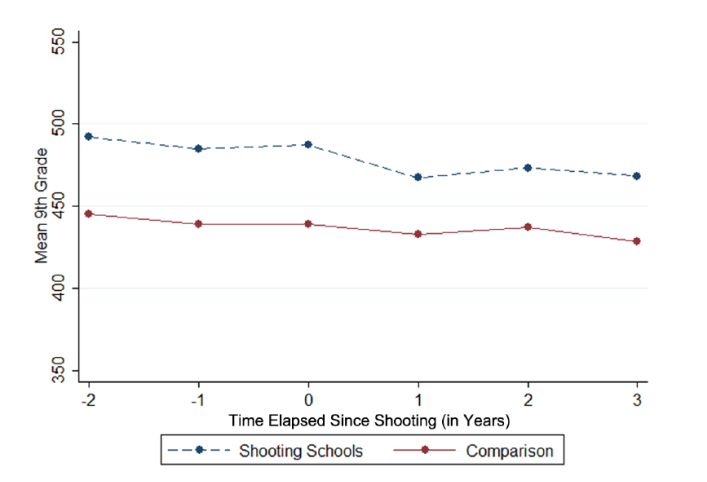

First, they examined whether enrollment in a school would go down after a shooting. (Note: all of the effects described apply to homicidal shootings. There were no effects of suicidal shootings on any of the outcomes.) They found that it did decrease, presumably as parents who could selected other schools. This effect was only observed in 9th grade enrollments, however. Perhaps families with children already attending a school felt more committed to that school.

Third, the researchers examined behavioral outcomes including graduation rates, attendances, and suspensions. They observed no effects.

On the one hand, it may seem unsurprising that school shootings affect academic outcomes three years later. On the other hand, there is a rich research literature showing that we often overestimate how long we’ll feel distressed in the face of a negative event. But in this case predictions of negative consequences are accurate. Attending a high school where a homicide takes place prompts trauma, and that impacts students school experience and achievement.

The needs of the students who remain at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School may be deemed less urgent that those of the immediate families of the slain. That’s a fair assessment. But the needs of the survivors are real, and we must ask how we can address them. And we must not forget the students who attend these schools where murder took place within the last three years:

- Marshall County High School

- Aztec High School

- Rancho Tehama Elementary School

- Freeman High School

- North Park Elementary School

- Townville Elementary School

- Alpine High School

- Jeremiah Burke High School

- Antigo High School

- Independence High School

- Mojave High School.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed