A new study indicates that people are somewhat more prone to be credulous when they think they are part of a group of readers.

Subjects read purported headlines from a news organization. The headlines covered a variety of topics, and they were evenly split for veracity. Subjects were asked to mark them as True or False, or to “flag” the fact, which indicated they would find out the truth or falsehood of that statement at the end of the series. Subjects got a small monetary reward when they were right and a same-size penalty when they were wrong. Raising the flag paid nothing in one experiment and a small reward in another.

The critical variable of interest is whether subjects thought they performed this task alone or with others, in which case they saw 100 or so other names of people they were told were doing the task at the same time. They were told their performance was not influenced by these other people; they just happened to be doing the task at the same time.

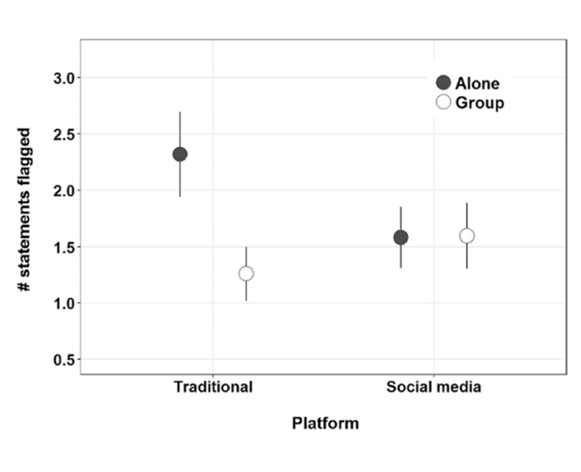

Across 8 experiments, there was a small but consistent bias to check facts less often if subjects thought other people performed the task too. Of the 8, the most interesting experiment was one where researchers changed the presentation format to make the headlines look like part of a Facebook feed. In that case, it didn’t matter whether they told subjects they were alone; the format was enough to make it feel social, as shown on the graph below.

1) Flagging something doesn’t signal “I want to know the answer.” It signals “I’m not sure.” So being in a group, you’re less sure of your answers because you unconscious think “in this big group, someone else really knows the answer, so I won’t pretend to know.” But the researchers collected confidence ratings when people said “true” or “false” and those didn’t differ between the answering alone and answerd with others conditions.

2) Social loafing. When you’re in a crowd, you figure others are doing at least some of the work (in this case, checking facts) so you don’t feel the need. To check on this, the researchers tried to make subjedts feel like they stood out in the group by making the subjects name on the screen red. This had no impact on the effect.

3) The presence of others makes it a social context, and taking people at their word is a social norm. But you would predict this would also make subjects say that more statements are true and they didn’t do this.

The researchers of a safety-in-numbers interpretation. When people are in a crowd, they feels safe; “there are lots of people here, so there’s no need to be vigilant, to gather more information. If there were a problem, someone would notice it.” The researchers offer some evidence for this: they found that people performed worse on a proof-reading task when they believed they were in a group.

This theory is certainly plausible. It calls to mind Jerry Clore's theory about the impact of emotion on cognition. Clore suggests that negative emotions (anger, sadness) put you in a mode to collect more information—things are not going well (hence the negative emotion) so you need more information, and to focus on details, to figure out what’s going wrong. When you’re happy, in contrast, you’re content to do the sort of thing you usually do in the current circumstance, i.e., to rely on memory and don’t worry so much about collecting new information. Everything is fine, so you keep doing what you’re doing.

That’s all very logical, but it certainly seems to create a difficult situation. If true, the we are all of us slightly more ready to believe anything we read on social media. No, logging into Instagram does not turn you into a credulous zombie—spend five minutes on Twitter, for example, and you’ll see as much disbelief (and anger) as you care for in a day. But the social nature of social media may be one of many contributing factors.

It highlights the fact that we are still working out the kinks in new media, trying to take advantage of the enormous increase in the our ability to create and to consume content while identifying and thwarting the drawbacks attendant to those increases.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed