In a way, this outcome seems odd. Practice is such an important part of certain types of skill, and much of homework is assigned for the purpose of practice. Why doesn't it help, or help more?

One explanation is that the homework assigned is not of very good quality, which could mean a lot of different things and absent more specificity sounds like a homework excuse. Another, better explanation is that practice doesn't do much unless there is rapid feedback, and that's usually absent at home.

A third explanation is quite different, suggesting that the problem may lie in measurement. Most studies of homework efficacy have used student self-report of how much time they spend on homework. Maybe those reports are inaccurate.

A new study indicates that this third explanation merits closer consideration.

The researchers (Rawson, Stahovich & Mayer, in press) examined homework performance among three classes of undergraduate engineering students taking their first statics course. The homework assigned was typical for this sort of course; the atypical feature was that students were asked to complete their homework with Smartpens. These function like regular ink pens, but when coupled with special paper, they record time-stamped pen strokes.

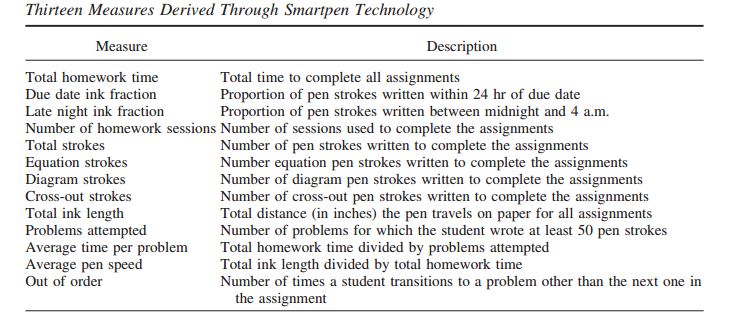

The researchers were able to gather objective measures of time spent on homework, as well as other performance metrics.

But the really interesting finding was a significant correlation of course grade and time spent on homework as measured by the Smartpen (r = .44) in the face of NO correlation between course grade and time spent on homework as reported by the students (r = -.16).

The relationship between homework and course grades is not the news. This is a college course and no matter what the format, it's only going to meet a few hours each week, and students will be expected to do a great deal of work on their own.

The news is that students were poor at reporting their time spent on homework; 88% reported more than the Smartpen showed they had actually spent. The correlation of actual time and reported time ranged from r = .16 to r = .35 for the three cohorts.

In other words, with such a noisy measure of time spent on homework, there was little hope of observing a reliable relationship of homework with a course outcome. This finding ought to call into question much of the prior research on homework.

Please don't take this blog posting as an enthusiastic endorsement of homework. For one thing, this literature seems pretty narrow in focusing solely on academic performance outcomes, given that many teachers and parents have other goals for homework such as increased self-directedness. For another thing, even if it were shown the certain types of homework led to certain types of improvement in academic outcomes, that doesn't mean every school and classroom ought to assign homework. That decision should be made in the context of broader goals.

But if teachers are going to assign homework, researchers should investigate its efficacy. This study should make us rethink how we interpret existing research in this area.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed