A recent meta-analysis (Richardson, Abraham, & Bond, 2012) gathered articles published between 1997 and 2010, the products of 241 data sets. These articles had investigated these categories of predictors:

- three demographic factors (age, sex, socio-economic status)

- five traditional measures of cognitive ability or prior academic achievement (intelligence measures, high school GPA, SAT or ACT, A level points)

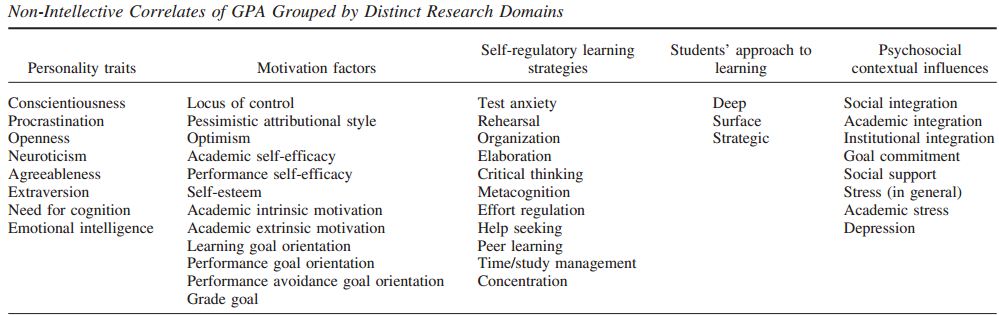

- No fewer than forty-two non-intellectual measures of personality, motivation, or the like, summarized into the categories shown in the figure below (click for larger image).

Let's start with simple correlations.

41 out of the 50 variables examined showed statistically significant correlations. But statistical significance is a product of the magnitude of the effect AND the size of the sample--and the samples are so big that relatively puny effects end up being statistically significant. So in what follows I'll mention correlations of .20 or greater.

Among the demographic factors, none of the three were strong predictors. It seems odd that socio-economic status would not be important, but bear in mind that we are talking about college students, so this is a pretty select group, and SES likely played a significant role in that selection. Most low-income kids didn't make it, and those who did likely have a lot of other strengths.

The best class of predictors (by far) are the traditional correlates, all of which correlate at least r = .20 (intelligence measures) up to r = .40 (high school GPA; ACT scores were also correlated r = .40).

Personality traits were mostly a bust, with the exception of consientiousness (r = .19), need for cognition (r = .19), and tendency to procrastinate (r = -.22). (Procrastination has a pretty tight inverse relationship to conscientiousness, so it strikes me as a little odd to include it.)

Motivation measures were also mostly a bust but there were strong correlations with academic self-efficacy (r = .31) and performance self-efficacy (r = .59). You should note, however, that the former is pretty much like asking students "are you good at school?" and the latter is like asking "what kind of grades do you usually get?" Somewhat more interesting is "grade goal" (r = .35) which measures whether the student is in the habit of setting a specific goal for test scores and course grades, based on prior feedback.

Self-regulatory learning strategies likewise showed only a few factors that provided reliable predictors, including time/study management (r = .22) and effort regulation (r = .32), a measure of persistence in the face of academic challenges.

Not much happened in the Approach to learning category nor in psychosocial contextual influences.

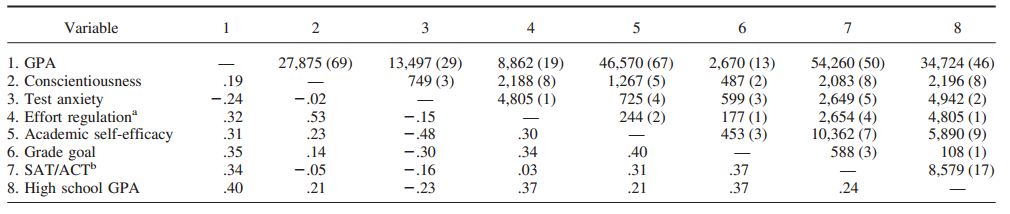

We would, of course, expect that many of these variables would themselves be correlated, and that's the case, as shown in this matrix.

The researchers first conducted five hierarchical linear regressions, in each case beginning with SAT/ACT, then adding high school GPA, and then investigating whether each of the five non-intellective predictors would add some predictive power. The variables were conscientiousness, effort regulation, test anxiety, academic self efficacy, and grade goal, and each did, indeed, add power in predicting college GPA after "the usual suspects" (SAT or ACT, and high school GPA) were included.

But what happens when you include all the non-intellective factors in the model?

The order in which they are entered matters, of course, and the researchers offer a reasonable rationale for their choice; they start with the most global characteristic (conscientiousness) and work towards the more proximal contributors to grades (effort regulation, then test anxiety, then academic self-efficacy, then grade goal).

As they ran the model, SAT and high school GPA continued to be important predictors. So were effort regulation and grade goal.

You can usually quibble about the order in which variables were entered and the rationale for that ordering, and that's the case here. As they put the data together, the most important predictors of college grade point average are: your grades in high school, your score on the SAT or ACT, the extent to which you plan for and target specific grades, and your ability to persist in challenging academic situations.

There is not much support here for the idea that demographic or psychosocial contextual variables matter much. Broad personality traits, most motivation factors, and learning strategies matter less than I would have guessed.

No single analysis of this sort will be definitive. But aside from that caveat, it's important to note that most admissions officers would not want to use this study as a one-to-one guide for admissions decisions. Colleges are motivated to admit students who can do the work, certainly. But beyond that they have goals for the student body on other dimensions: diversity of skill in non-academic pursuits, or creativity, for example.

When I was a graduate student at Harvard, an admissions officer mentioned in passing that, if Harvard wanted to, the college could fill the freshman class with students who had perfect scores on the SAT. Every single freshman-- 800, 800. But that, he said, was not the sort of freshman class Harvard wanted.

I nodded as though I knew exactly what he meant. I wish I had pressed him for more information.

References:

Richardson, M., Abraham, C., Bond, R. (2012). Psychological correlates of university students' academic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138, 353-387.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed