New York Times blog: Young people frequent libraries, study says.

Christian Science Monitor: Millenials: A rising generation of book lovers.

NPR (Boston): Facebook generation is reading strong.

Sexy stuff, but I think it's misleading.

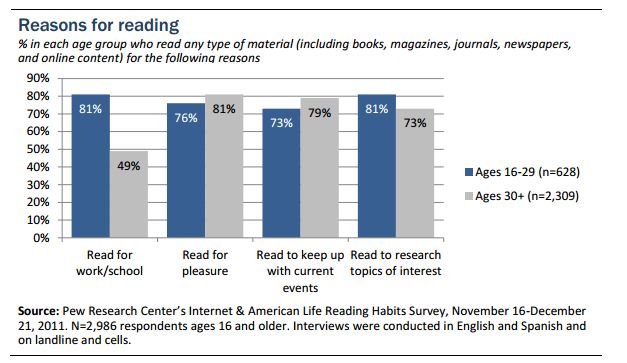

One message is that young people are reading "a lot." What constitutes "a lot" is a judgement call, obviously, but in this study the data showed that 83% of 18-29 year-olds had a read a book sometime in the previous year. That strikes me as a low bar to be considered "a reader."

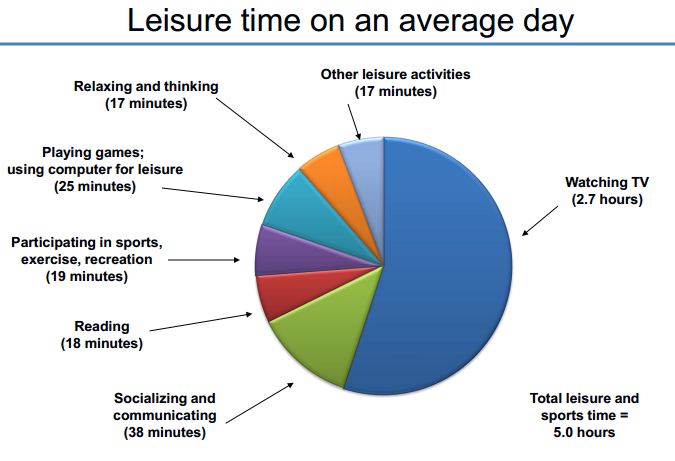

Other data show that Americans spend much more time watching television each day than they do reading. This chart is from the Bureau of Labor Statistics

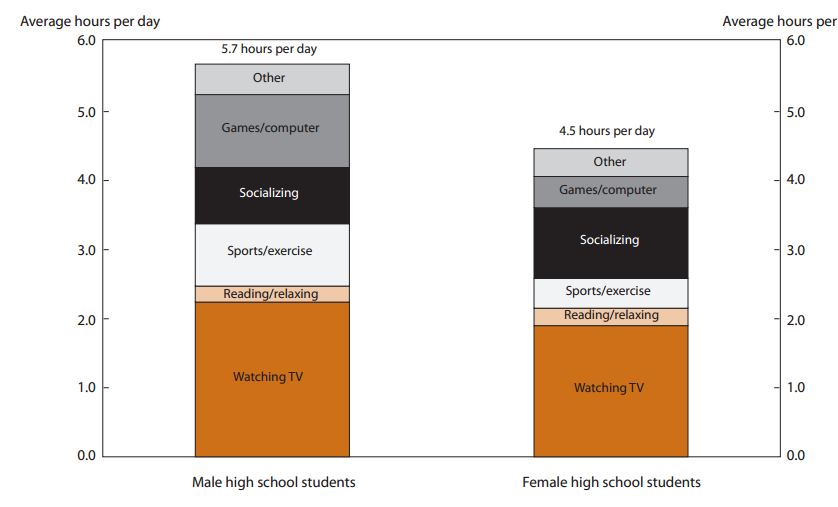

The study did report these data separately, shown below.

Likewise, the increased use of libraries by young respondents is likely mediated by their need to use libraries for schoolwork.

There have been many reports of American reading habits in the last fifty years, and especially in the last twenty. The overall picture is that reading dropped when television became widely available, and hasn't changed much since then.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed