My sense is that most teachers and parents think that manipulatives help a lot. I could not locate any really representative data on this point, but the smaller scale studies I've seen support the impression that they are used frequently. In one study of two districts the average elementary school teacher reported using manipulatives nearly every day (Uribe-Florez & Wilkins, 2010).

The authors analyzed the results of 55 studies that compared instruction with or without manipulatives. The overall effect size was d = .37--typically designated a "moderate" effect.

But there were big differences depending on content being taught: for example, the effect for fractions was considerable larger (d = .69) than the effect for arithmetic (d = .27) or algebra (d = .21).

More surprising to me, the effect was largest when the outcome of the experiment focused on retention (d = .59), and was relatively small for transfer (d = .13).

What are we to make of these results? I think we have to be terribly cautious about any firm take-aways. That's obvious from the complexity of the results (and I've only hinted at the number of interactions).

It also seems obvious that manipulatives can be more or less useful depending on how effectively they are used. For example, some fine-grained experimental work indicates the effectiveness of using a pan-balance as an analogy for balancing equations depends on fairly subtle features of what to draw students’ attention to and when (Richland et al, 2007).

My hunch is that at least one important source of variability (and one that's seldom measured in these studies) is the quality and quantity of relevant knowledge students have when the manipulative is introduced. For example, we might expect that the student with a good grasp of the numerosity would be in a better position to appreciate a manipulative meant to illustrate place value than the student whose grasp is tenuous. Why?

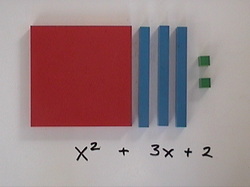

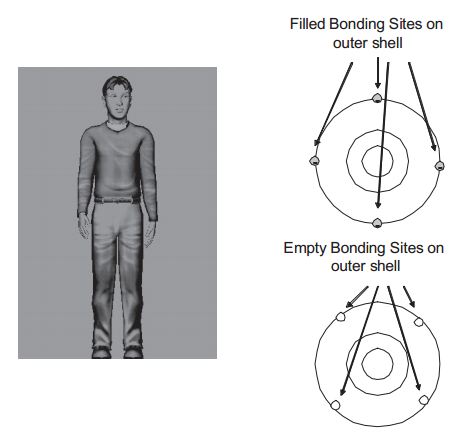

David Uttal and his associates (Uttall, et al, 2009) emphasized this factor when they pointed out that the purpose of a manipulative is to help students understand an abstraction. But a manipulative itself is an abstraction—it’s not the thing-to-be-learned, it’s a representation of that thing—or rather, a feature of the manipulative is analogous to a feature of the thing-to-be-learned. So the student must simultaneously keep in mind the status of the manipulative as concrete object and as a representation of something more abstract. The challenge is that keeping this dual status in mind and coordinating them can be a significant load on working memory. This challenge is potentially easier to meet for those students who firmly understand concepts undergirding the new idea.

I’m generally a fan of meta-analyses. I think they offer a principled way to get a systematic big picture of a broad research literature. But the question “do manipulatives help?” may be too broad. It seems too difficult to develop an answer that won’t be mostly caveats.

So what’s the take-away message? (1) manipulatives typically help a little, but the range of effect (hurts a little to helps a lot) is huge; 2) researchers have some ideas as to why manipulatives work or don’t work. . .but not in a way that offers much help in classroom application.

This is an instance where a teacher’s experience is a better guide.

References

Carbonneau, K. J., Marley, S. C., & Selig, J. P. (in press). A meta-analysis of the efficacy of teaching mathematics with concrete manipulatives. Journal of Educational Psychology. Advance online publication.

Richland, R. E. Zur, O. Holyoak, K. J. (2007). Cognitive Supports for Analogies in the Mathematics Classroom, Science, 316, 1128–1129.

Uribe‐Flórez, L. J., & Wilkins, J. L. (2010). Elementary school teachers' manipulative use. School Science and Mathematics, 110, 363-371.

Uttal, D. H., O’Doherty, K., Newland, R., Hand, L. L., & DeLoache, J.

(2009). Dual representation and the linking of concrete and symbolic

representations. Child Development Perspectives, 3, 156–159.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed