If I asked "what are the consequences of retrieval practice to memory?" the question sounds silly...I just said it makes memory better. "Better" sounds like it means stronger, more robust, easier to get out of memory, more likely to last.

A recent study (Sutterer & Awh, 2016) separated two aspects of memory improvement: likelihood of retrieving the memory at the right time and precision of the memory.

Previous studies of the retrieval practice effect have confounded those aspects of memory by using binary stimuli; if the to-be-remembered item is "la montre" when I see the word "watch," there's no opportunity to show that the memory has become more precise...I either remember it or I don't. Maybe the memory representation did get more precise, and that made it more distinctive in memory and therefore easier to find...or maybe retrieval practice didn't make my memory for "la montre" more precise at all, but made the memory more accessible.

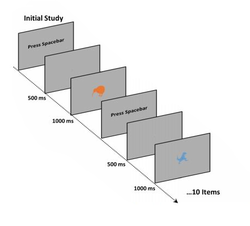

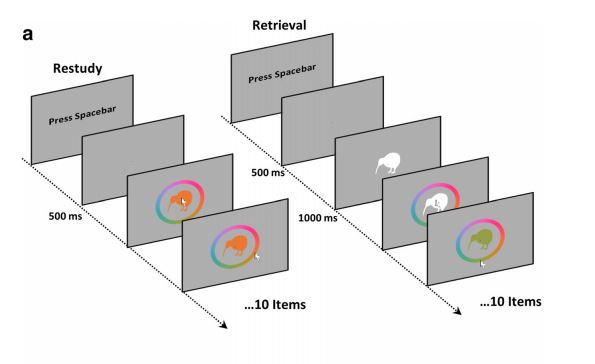

Instead of binary stimuli, Sutterer & Awh used stimuli that differed on a continuous scale. The stimuli were silhouettes of familiar objects in different colors. Subjects were to associate the color with the object.

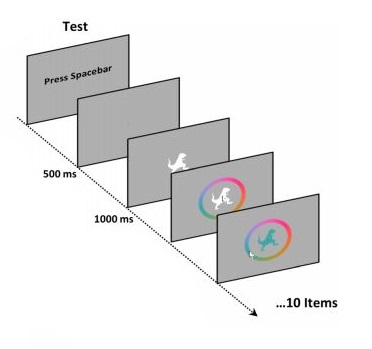

In the final session everyone's memory for the colors was tested.

Of course we can't see what the subject is thinking...we only know they pick something on the color wheel. But it's possible to fit a mathematical model to the responses, assuming that the distribution of responses will be uniform for guesses (that is, they are guessing randomly) and normal (i.e., bell-shaped) for correct responses. The observed responses are a mix of these distributions.

The modelling doesn't allow us to say whether any one individual response is a guess or not, but using all the data we can characterize the two distributions.

Retrieval practice might either (1) increase the proportion of responses that are correct (and decrease the number of guesses) OR increase the precision of correct responses (i.e., make the distribution of correct responses tighter around the target value). Or both.

The results showed that retrieval practice had no impact on memory precision at all. It made correct memories more accessible. You were more likely to remember that the kiwi was sort of an orange color, but not to get closer to the exact shade of orange. A followup experiment showed the same results were observed if the test occurred after a 24 hour delay.

What's the implication for classroom practice? Nothing, as yet. This is just one study. But there are things that teachers want students to know that we might think of as continuous (like color) rather than discrete (like a color label). One example might be aspects of "depth" of vocabulary (Perfetti, 2007) or the relationship of numerosity and space (Hubbard et. al, 2005).

It makes some intuitive sense that retrieval practice can make it easier to get to a memory that's already in there, but can't further fine tune the memory, make it more precise.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed