But there is less research on the topic than you'd think, and much of it (e.g., May, Huff, & Goldring, 2012) actually shows a weak or non-existent relationship between student achievement and the priority administrators place on instructional leadership (as opposed to other aspects of a principal's job, e.g., close attention to administrative matters, inspirational leadership, focus on school culture, etc.).

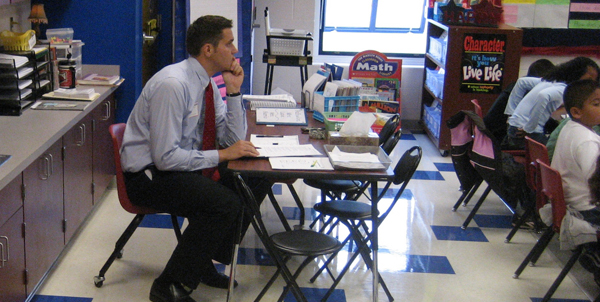

A terrific new study by Jason Grissom, Susanna Loeb, and Ben Master shed light on the role of instructional leadership. It's the method that sets this study apart. Instead of simply asking principals "how important is instructional leadership to you?" or having them complete time diaries, researchers actually followed 100 principals around for a full school day, recording what they did.

The researchers also had access to administrative data from the district (Miami-Dade county) about principals, teachers, and students that could be linked to the observational data. The outcome measure of interest was student learning gains, as measured by standardized tests.

The results showed that principals spent, on average, 12.6 percent of their time on activities related to instruction. The most common was classroom walkthroughs (5.4%) and the second was formal teacher evaluation (2.4%).

As to the primary question of the study, time spent on instructional leadership was NOT associated with student learning outcomes.

But once "instructional leadership" was made more fine-grained, the picture changed.

Time spent coaching teachers--especially in math--was associated with better student outcomes. So was time spent evaluating teachers and curriculum.

But informal classroom walkthroughs--the most common activity--were negatively associated with student achievement. This was especially true in high schools.

In a follow-up analysis, the researchers evaluated these data in light of what the principals said about how teachers view classroom walkthroughs. The negative association with student achievement was most evident where principals believed that teachers did not view walkthroughs as opportunities for professional development. (Other reasons for walkthroughs might be to ensure that a teacher is following a curriculum, or to be more visible to faculty.)

Although the researchers suggest that their results should be considered exploratory, they do suggest a general principle of instructional leadership that fits well with one overarching principle of learning: feedback is essential. Instructional leadership activities that offer meaningful feedback to teachers may help. Those that don't, will not.

Grissom, J. A., Loeb, S., & Master, B. (2013). Effective instructional time use for school leaders: Longitudinal evidence from observations of principals. Educational Researcher, 42, 433-444.

May, H., Huff, J., & Goldring, E. (2012). A longitudinal study of principals' activities and student performance. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 23, 417-439.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed