The last time I blogged on this topic Cedar Riener remarked that it's sort of silly to frame the question as "does gaming work?" It depends on the game.

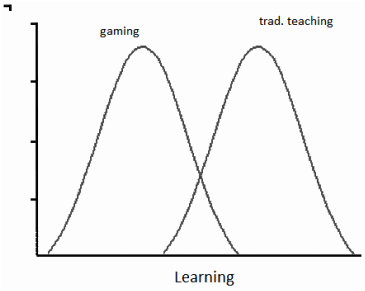

The category is so broad it can include a huge variety of experiences for students. If there were NO games from which kids seemed to learn anything, you probably ought not to conclude "kids can't learn from games." To do so would be to conclude that distribution of learning for all possible games and all possible teaching would look something like this.

So what's the point of a meta-analysis that poses the question "do kids learn more from gaming or traditional teaching?

I think of these reviews not as letting us know whether kids can learn from games, but as an overview of where we are--just how effective are the serious games offered to students?

The headline results featured in the abstract is "games work!" Games are reported to be superior to conventional instruction in terms of learning (d = 0.29) and retention (d = .36) but somewhat surprisingly, not motivation (d = .26).

The authors examined a large set of moderator variables and this is where things get interesting. Here are a few of these findings:

- Students learn more when playing games in groups than playing alone.

- Peer-reviewed studies showed larger effects than others. (This analysis is meant to address the bias not to publish null results. . . but the interpretation in this case was clouded by small N's.)

- Age of student had no impact.

But two of the most interesting moderators significantly modify the big conclusions.

First, gaming showed no advantage over conventional instruction when the experiment used random assignment. When non-random assignment was used, gaming showed a robust advantage. So it's possible (or even likely) that games in these studies were more effective only when they interacted with some factor in the gamer that is self-selected (or selected by the experimenter or teacher). And we don't know yet what that factor is.

Second the researchers say that gaming showed and advantage over "conventional instruction" but followup analyses show that gaming showed no advantage over what they called "passive instruction"--that it, the teacher talk or reading a textbook. All of the advantage accrued when games were compared to "active instruction," described as "methods that explicitly prompt learners to learning activities (e.g., exercises, hypertext training.)" So gaming (in this data set) is not really better than conventional instruction; it's better than one type of instruction (which in the US is probably less often encountered.)

So yeah, I think the question in this review is ill-posed. What we really want to know is how do we structure better games? That requires much more fine-grained experiments on the gaming experience, not blunt variables. This will be painstaking work.

Still, you've got to start somewhere and this article offers a useful snapshot of where we are.

EDIT 5:00 a.m. EST 2/11/13. In the original post I failed to make explicit another important conclusion--there may be caveats on when and how the games examined are superior to conventional instruction, but they were almost never worse. This is not an unreasonable bar, and as a group the games tested pass it.

Wouters, P, van Nimwegen, C, van Oostendorp, H., & van der Spek, E. G. (2013). A meta-analysis of the cognitive and motivational effects of serious games. Journal of Educational Psychology. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1037/a0031311

RSS Feed

RSS Feed