The researchers examined the spontaneous use by children of relational reasoning—the ability to make different sorts of comparisons of mental entities. This was a relatively small sample, about 20 children (ages five to seventeen) sorted into three groups: early (K-2), middle (fourth-eighth grade) and late (tenth and eleventh grade). To examine reasoning, each child had a one-on-one conversation with a researcher. The researcher showed the child a juice box, and prompted a conversation about its design, with questions like “Why had this product been developed,” and “What materials have been used to make the packaging?” Then the researcher did the same thing with an unfamiliar object—a vegetable cutter—and asked them “What do you think this is?” and “Why do you think this?” Conversations averaged around 5 and a half minutes for each and were recorded for later analysis.

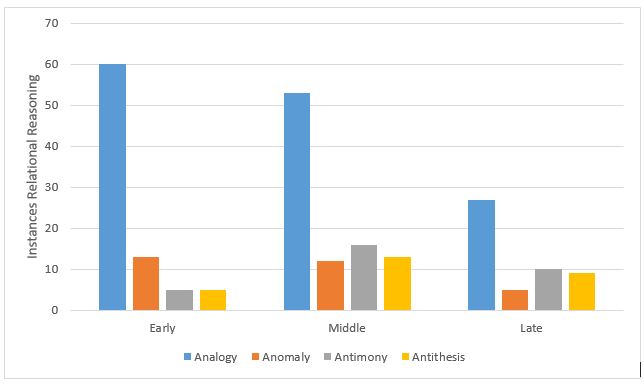

The figure shows the instances of relational reasoning.

A couple of findings are noteworthy. Proportionally, the middle group verbalized relational reasoning more often than either the early or late group. And different types of relational reasoning were used more or less by different groups: early children were less likely to use antimony and antithesis, and late children were less likely than others to use analogy.

But also notable is that all types of relational reasoning were used by children of all groups, which included children as young as five. What’s notable to me is that children in this experiment were not presented with an instance of reasoning to see if they could understand it, nor were they presented with a problem that could only be solved by using the type of reasoning of interest. Rather, they were given a very open-ended problem to see if they would spontaneously use relational reasoning.

There are two drawbacks to this study. First, it’s possible that experimenters were, unwittingly, drawing out relational reasoning statements through their ends of the conversation. Second, the researchers reported that they sampled children to represent a spectrum of individual differences: gender, ethnicity, socio-economic status, quality of school attended, and others. But the data were not analyzed using these variables. Given the small N, it’s plausible that a few kids from particular schools carried most of the observed effect.

Despite these drawbacks, I think the study is interesting because it fits with the larger pattern described elsewhere and that seem to be underappreciated: children engage a variety of reasoning strategies from an early age.

Jablansky, S., Alexander, P. A., Dumas, D., & Compton, V. (in press) Journal of Educational Psychology. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/edu0000070.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed