The answer is “they can and they do.” But there is an important caveat on this conclusion. Beth Marsh and her colleagues offer an excellent summary of this research in a new article published in Educational Psychology Review.

The advantage of fiction is that the narrative can engage students, transport them into the story. The fear is that readers will assume that information in fiction is true, whereas fiction may well contain inaccuracies. We don’t expect fiction to be vetted for accuracy the way a non-fiction source would be. (Certainly Hollywood movies are notorious for playing fast-and-loose with the truth.)

Isn’t it possible, then, that these inaccuracies would be later remembered by subjects as true?

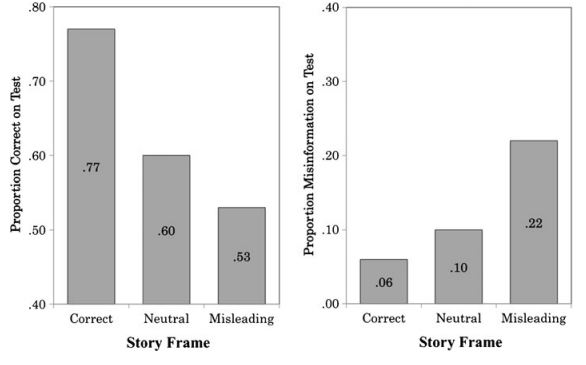

Yes. In her experiments Marsh uses short stories that refer to facts about the world. The facts are either accurate (it happened on the largest ocean, the Pacific) inaccurate (it happened on the largest ocean, the Atlantic) or in a control condition, absent (it happened on the largest ocean).

Later, subjects take a general information test that includes a probe of the target information (Which is the largest ocean on earth?) . The question is whether reading the accurate or inaccurate information influences subjects’ response to the question (compared to the control condition).

Thus, students are influenced by inaccurate information (at least for the duration of the experiment, as long as a week) and prior knowledge is not protective. In other words, the misleading information has an impact even for stuff that most of the students knew before the experiment started.

Even more alarming, a general warning “there may be misinformation here” was not effective (Marsh & Fazio, 2006). It may be that readers are caught up in the narrative and don’t worry overmuch about evaluating each bit of factual content they come across.

The good news is that a specific warning telling subjects exactly which bit of information cannot be trusted is very effective in preventing subjects from absorbing the inaccuracy into their beliefs (Butler et al 2009).

And “absorbing” is the right word: typically, readers later report that they “knew” the inaccurate information before the start of the experiment.

So, can fictional sources be used to help students learn new knowledge about the world? Yes, but teachers must be aware that the inaccuracies may be learned as well, and ideally they will inoculate students against inaccuracies with specific warnings.

Butler, A. C., Zaromb, F., Lyle, K. B., & Roediger, H. L., III. (2009). Using popular films to enhance classroom learning: The good, the bad, and the interesting. Psychological Science, 20, 1161–1168.

Marsh, E. J., Butler, A. C. & Umanath, S. (2012) Using fictional sources in the classroom: Applications from cognitive psychology. Educational Psychology Review, 24, 449-469.

Marsh, E. J., & Fazio, L. K. (2006). Learning errors from fiction: Difficulties in reducing reliance on fictional stories. Memory & Cognition, 34, 1140–1149.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed