- Humans inhabit almost every corner of the globe. Diversity of tribes’ behavior is a product of environmental diversity and the fact that humans are so good at problem-solving. Different environments prompt different behaviors, but even when environments are similar people are so ingenious they come up with different solutions to the same environmental challenges.

- Diversity of behavior is due to cultural traditions. Sure, there are some environmental constraints on what I do—people living in the desert won’t fish—but diversity is so high because small changes are preserved with fidelity. People keep doing what the tribe has always done.

The first account predicts that local environmental conditions will determine tribe behaviors. Two predictions may be drawn from the second of these accounts: (1) tribes that live spatially near one another will be more behaviorally similar and; (2) behaviors will persist across generations.

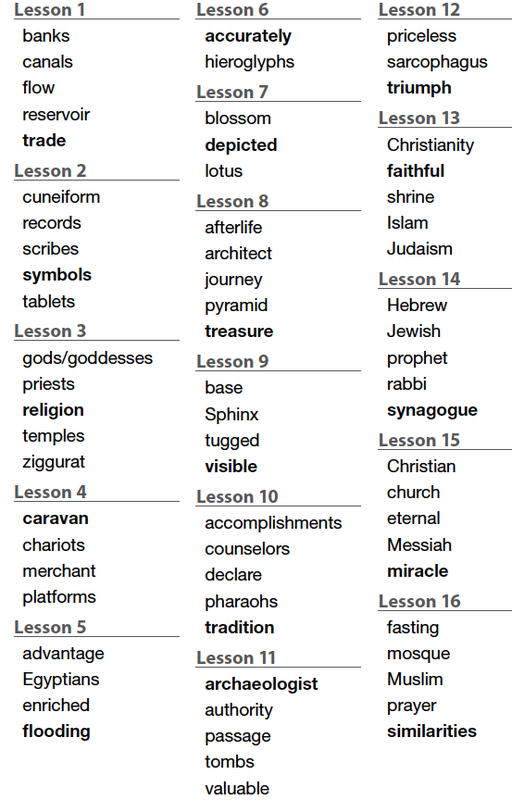

A recent study sought to test both predictions using an enormous dataset of 172 tribes in western North America. The dataset records 297 behavioral variables (e.g., what people eat, their religious practices, family organization, and so on) and 133 variables concerning the environment (available flora & fauna, characteristics of soil, altitude, precipitation, etc.). All data represent practices and conditions at the time the tribe first encountered Europeans.

Spatial distance between tribes is simple enough to measure. The researchers used language phylogeny as a proxy of cultural phylogeny. Analyses of the similarity of languages yields an “evolutionary tree” of languages, so the distance of any two languages on the tree can be measured with a “most recent common ancestor” approach.

The question of interest is which of three variables predicts whether two tribes show similar behaviors. If behavior is mostly a matter of smart individuals adapting to the local ecology, then tribes inhabiting similar terrain should behave similarly. But if learning is mostly social, then tribes that are physically and/or culturally close should be more likely to behave similarly.

The results showed that cultural history and ecology both affect everything…but cultural history generally has the stronger effect. Within cultural history, phylogeny mattered more than spatial distance.

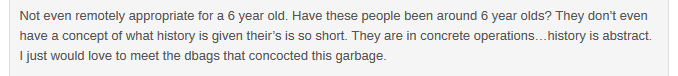

This analysis is about group behaviors, things that most people in a tribe do. But the result showing the importance of social learning may hold a lesson for those of us who think about the education of individuals. It’s easy to be a little dazzled by the brilliance of the human mind, and to see most of cognitive development as the intrepid mind of the individual, exploring the environment like a little scientist.

That’s certainly the emphasis we get from many psychologists. Bandura’s social learning duly noted, the towering figure of Piaget puts the child’s individual discoveries at the center of learning.

When it comes to schooling, I sometimes sense a similar reverence for learning that is the product of an individual mind at work, over the mere copying of someone else’s solution. It’s true that you only get true invention/innovation from original thought. But it’s a whole lot quicker and more reliable to copy what others have done. That is probably why social learning seems to be the workhorse of cultural learning.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed