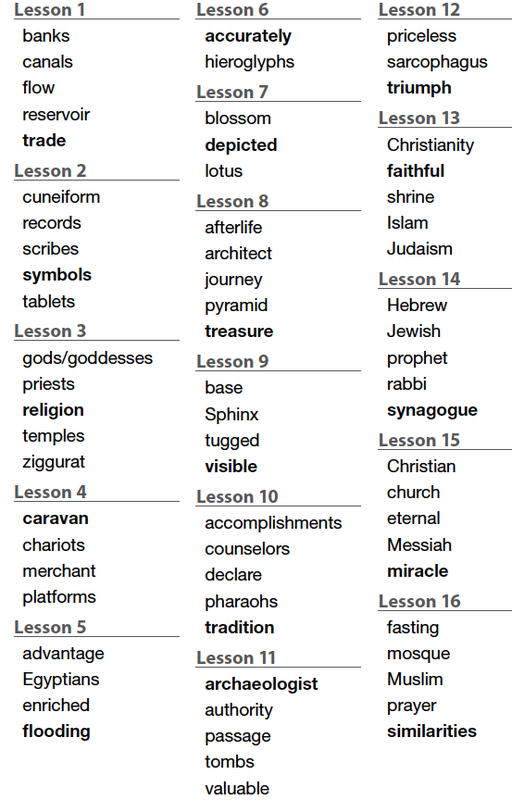

The New York State Education Dept. has a website that is meant to help teachers prepare for the Common Core Standards. Author Chris Cerrone posted a bit of a 1st grade curriculum module on early civilizations. Here it is:

The responses in the 78 comments were nearly uniformly negative. As you might expect from that volume of commentary, the criticisms were wide-ranging, much of it directed more generally at standardized testing and the idea of the CCSS themselves.

But a lot of the commentary concerned cognitive development, and I want to focus there. This comment was typical (click for larger image).

So lessons would be developmentally inappropriate if they demanded a type of thinking that the child was simply incapable of, given his developmental stage.

I have argued in some detail that stage theories have two major problems: first, data from the last twenty years or so make development look like it's continuous, rather than occurring in discrete stages. Second, children's cognition is fairly variable day to day, even when the same child tries the same task.

I have argued elsewhere that trying to take a psychological finding and using it to draw strong conclusions about instruction--including what children are, in principle, ready for--is fraught with problems. How much the more is that true when using a psychological theory rather than an experimental finding.

So if Piaget will not be our guide as to what 1st graders are ready for, what should be?

The experience of early elementary educators, of course, and some of the people commenting on the blog posting are or were first grade teachers. And almost unanimously, they thought this material was inappropriate for first graders. (Some thought kids this age shouldn't be learning about other religions at this age. No argument there, that's a matter of ones values. I'm only talking about what kids can cognitively handle.)

But if we adopt a proof-of-the-pudding-is-in-the-eating criterion, lessons on ancient civilizations are fine because they are in use and children are learning. The material shown above is part of the Core Knowledge sequence, around for more than a decade and used by over a thousand schools. (NB: I'm on the Board of the Core Knowledge Foundation.)

And Core Knowledge is not alone. Another curriculum has had first-graders learn about ancient civilizations not for a decade, but for about a century: Montessori. (NB again: my children experienced these lessons at their school, and my wife teaches them--she's an early elementary Montessori teacher.)

Montessori schools teach the same "Five Great Lessons" at the beginning of first, second, and third grades. They are

- The history of the universe and earth

- The coming of life

- The origins of human beings

- The history of signs and writing

- The story of numbers and mathematics

Photo from milwaukee-montessori.org

Photo from milwaukee-montessori.org If it seems impossible or highly unlikely to you that 6 year olds could really get anything out of such lessons, I'll ask you to consider this. Our understanding of any new concept is always incomplete.

For example, how do children learn that some people they hear about (Peter Pan) are made up and never lived, whereas others (the Pharaohs) were real? Not by an inevitable process of neurological maturation that makes their brain "ready" for this information, whereupon they master it quickly. They learn it bit by bit, in fits and starts, sometimes seeming to get it, other times not.

And you can't always wait until children are "ready." Think about mathematics. Children are born understanding numerosity, but they understand it on a logarithmic scale--the difference between five and ten is larger than the difference between 70 and 75. To understand elementary mathematics they must learn to think of numbers of a linear scale. In this case, teachers have to undo Nature. And if you wait until the child is "developmentally ready" to understand numbers this way, you'll never teach them mathematics. It will never happen.

In sum, I don't think developmental psychology is a good guide to what children should learn; it provides some help in thinking about how children learn. The best guide to "what" is what children know now, and where you want their learning to head.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed