I (like everyone else) am always eager for documents that clearly summarize a large, complex literature. One such literature of urgent interest is the role of self-regulation in academic success. A new working paper from Transforming Education (full disclosure: I’m on their advisory board) does a great job of highlighting the important findings regarding non-cognitive skills, a not-very-precise term originating in economics that refers mostly to self-control and social competence.

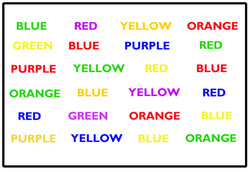

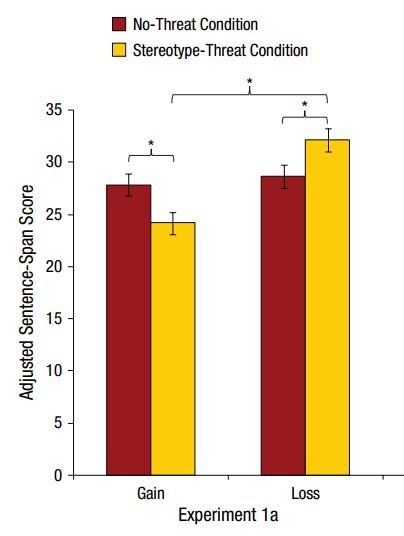

"Stereotype threat" refers to a phenomenon in which people perform worse on tasks (especially mental tasks) in line with stereotypes, if they are are reminded of this stereotype. Hence, the stereotype for women (in American culture) is that they are not as good at math as men; for older people, that they are more forgetful than the young; and for African-Americans, that they are less proficient at academic tasks. Members of each group do indeed perform worse at that type of task if the stereotype is made salient just before they undertake it (e.g. Appel & Kronberger, 2012). Why does it happen? Most researchers have thought that the mechanism is via working memory. When the stereotype becomes active, people are concerned that they will verify the stereotype. These fears occupy working memory, thereby reducing task performance (e.g., Hutchison, Smith & Ferris, 2013). But a new experiment offers an alternative account. Sarah Barber & Mara Mather (2013) suggests that stereotype threat might operate through a mechanism called regulatory fit. That's a theory of how people pursue goals. If the way you conceive of task goals matches the goal structure of the task, you're more likely to do well than if it's a poor fit.  Stereotype threat makes you focus on prevention; you don't want to make mistakes (and thus confirm the stereotype). But, Barber & Mather argue, most experiments emphasize doing well, not avoiding mistakes. Thus, you'd be better off with a promotion focus, not a prevention one. To test this idea, Barber & Mather tested fifty-six older (around age 70) subjects on a combined memory/working memory task. Subjects read sentences, some of which made sense, others which were nonsensical either syntactically or semantically. Subjects indicated with a button press whether the sentence made sense or not. In addition, they were told to remember the last word of the sentence for as many of the sentences as they could. Task performance was measured by a combined score: how many sentences were correctly identified (sensible/nonsensical) and how many final words were remembered. Next, subjects read one of two fictitious news articles. The one meant to invoke stereotype threat described the loss of memory due to aging. The control article described preservation of memory with aging. Then, subjects performed the sentence task again. We would expect that stereotype threat would lead to worse performance. BUT the experimenters also varied the reward structure of the task. Some subjects were told they would get a monetary reward for good performance. Others were told they were starting with a set amount of money, and that each memory error would incur a penalty. The instructions made a big difference in the outcome. As shown in the graph, framing in terms of costs for errors didn't just remove stereotype threat; it actually lead to an improvement. This outcome makes sense, according to the regulatory fit hypothesis. Subjects were worried about errors, and the task rewarded them for avoiding errors. These data are the first to test this new hypothesis as to the mechanism of stereotype threat, and should not be seen as definitive. But if this new explanation holds up (and if it applies to other groups) it should have significant implications for how threat can be avoided. References: Appel, M., & Kronberger, N. (2012). Stereotypes and the achievement gap: Stereotype threat prior to test taking. Educational Psychology Review, 24(4), 609-635. Barber, S. J., & Mather, M. (2013). Stereotype Threat Can Both Enhance and Impair Older Adults’ Memory. Psychological science, published online Oct. 22, 2013. DOI: 10.1177/0956797613497023. Hutchison, K. A., Smith, J. L., & Ferris, A. (2013). Goals Can Be Threatened to Extinction Using the Stroop Task to Clarify Working Memory Depletion Under Stereotype Threat. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 4(1), 74-81. I finally got around to reading Paul Tough's How Children Succeed. If you haven't read it yet, I recommend that you do. You probably know by now the main message: what really counts for academic success is conscientiousness (or its close cousins, grit, or character or non-cognitive skills). Tough intersperses explanations of the science behind these concepts with stories of students that he's met and followed. The stories add texture and clarity, and Tough is among a very small number of reporters who gets complex science right consistently. He takes you through attachment theory, the HPA axis, and executive control functions, all without losing his footing nor prompting glazing in the reader's eyes. Tough also devotes considerable space to a fascinating inside look at how charter school mavens have thought about self-control, how their thinking has changed over time, and how their views square with the science.  The only flaws I see in the book concern a couple of big-picture conclusions that Tough draws. First, there's what Tough calls the cognitive hypothesis--that academic success is driven primarily (perhaps even solely) by cognitive skills. The book suggests that this premise may be in error. What really counts is self-control. But of course, you do need cognitive skills for academic success. In fact, Tough describes in detail the story of a boy who is very gritty indeed when it comes to chess, and who scales great heights in that world. But he's not doing all that well in school, and a teacher who tries to tutor him is appalled by what he does not know. Self-control predicts academic success because it makes you more likely to do the work to develop cognitive skills. I'm sure Tough understands this point, but a reader could easily miss it. Second, Tough closes the book with some thoughts on education reform. This section, though brief, struck me as unnecessary and in fact ill-advised. The whole book is about individual children and what makes them tick. Jumping to another level of analysis--policy--can only make this speculation seem hasty. But these two minor problems are mere quibbles. If you have heard about "non-cognitive skill," or "self-control" or "grit" and wonder whether there's anything to it, you'd be hard put to find a better summary than How Children Succeed. The cover story of latest New Republic wonders whether American educators have fallen in blind love with self-control. Author Elizabeth Weil thinks we have. Titled “American Schools Are Failing Nonconformist Kids: In Defense of the Wild Child” the article suggests that educators harping on self-regulation are really trying to turn kids into submissive little robots. And they do so because little robots are easier to control in the classroom. But lazy teachers are not the only cause. Education policy makers are also to blame, according to Weil. She writes that “valorizing self-regulation shifts the focus away from an impersonal, overtaxed, and underfunded school system and places the burden for overcoming those shortcomings on its students.”  And the consequence of educators’ selfishness? Weil tells stories that amount to Self-Regulation Gone Wild. A boy has trouble sitting cross-legged in class—the teacher opines he should be tested because something must be wrong with him. During story time the author’s daughter doesn’t like to sit still and to raise her hand when she wants to speak. The teacher suggests occupational therapy. I can see why Weil and her husband were angry when their daughter’s teacher suggested occupational therapy simply because the child’s behavior was an inconvenience to him. But I don’t take that to mean that there is necessarily a widespread problem in the psyche of American teachers. I take that to mean that their daughter’s teacher was acting like a selfish bastard. The problem with stories, of course, is that there are stories to support nearly anything. For every story a parent could tell about a teacher diagnosing typical behavior as a problem, a teacher could tell a story about a child who really could do with some therapeutic help, and whose parents were oblivious to that fact. What about evidence beyond stories? Weil cites a study by Duncan et al (2007) that analyzed six large data sets and found social-emotional skills were poor predictors of later success. She also points out that creativity among American school kids dropped between 1984 and 2008 (as measured by the Torrance Test of Creative Thinking) and she notes “Not coincidentally, that decrease happened as schools were becoming obsessed with self-regulation.” There is a problem here. Weil uses different terms interchangeably: self-regulation, grit, social-emotional skills. They are not same thing. Self-regulation (most simply put) is the ability to hold back an impulse when you think that that the impulse will not serve other interests. (The marshmallow study would fit here.) Grit refers to dedication to a long-term goal, one that might take years to achieve, like winning a spelling bee or learning to play the piano proficiently. Hence, you can have lots of self-regulation but not be very gritty. Social emotional skills might have self-regulation as a component, but it refers to a broader complex of skills in interacting with others. These are not niggling academic distinctions. Weil is right that some research indicates a link between socioemotional skills and desirable outcomes, some doesn’t. But there is quite a lot of research showing associations between self-control and positive outcomes for kids including academic outcomes, getting along with peers, parents, and teachers, and the avoidance of bad teen outcomes (early unwanted pregnancy, problems with drugs and alcohol, et al.). I reviewed those studies here. There is another literature showing associations of grit with positive outcomes (e.g., Duckworth et al, 2007). Of course, those positive outcomes may carry a cost. We may be getting better test scores (and fewer drug and alcohol problems) but losing kids’ personalities. Weil calls on the reader’s schema of a “wild child,” that is, an irrepressible imp who may sometimes be exasperating, but whose very lack of self-regulation is the source of her creativity and personality.  But irrepressibility and exuberance is not perfectly inversely correlated with self-regulation. The purpose of self-regulation is not to lose your exuberance. It’s to recognize that sometimes it’s not in your own best interests to be exuberant. It’s adorable when your six year old is at a family picnic and impulsively practices her pas de chat because she cannot resist the Call of the Dance. It’s less adorable when it happens in class when everyone else is trying to listen to a story. So there’s a case to be made that American society is going too far in emphasizing self-regulation. But the way to make it is not to suggest that the natural consequence of this emphasis is the crushing of children’s spirits because self-regulation is the same thing as no exuberance. The way to make the case is to show us that we’re overdoing self-regulation. Kids feel burdened, anxious, worried about their behavior. Weil doesn’t have data that would bear on this point. I don’t either. But my perspective definitely differs from hers. When I visit classrooms or wander the aisles of Target, I do not feel that American kids are over-burdened by self-regulation. As for the decline in creativity from 1984 and 2008 being linked to an increased focus on self-regulation…I have to disagree with Weil’s suggestion that it’s not a coincidence (setting aside the adequacy of the creativity measure). I think it might very well be a coincidence. Note that scores on the mathematics portion of the long-term NAEP increased during the same period. Why not suggest that kids improvement in a rigid, formulaic understanding of math inhibited their creativity? Can we talk about important education issues without hyperbole? References Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., & Kelly, D. R. (2007). Grit: perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of personality and social psychology, 92(6), 1087. Duncan, G. J., Dowsett, C. J., Claessens, A., Magnuson, K., Huston, A. C., Klebanov, P., ... & Japel, C. (2007). School readiness and later achievement. Developmental psychology, 43(6), 1428.  Suppose a high school student cheats on a test. How harshly should a parent or teacher treat this offense? The efficacy of punishment in such situations has been controversial, and a new study sheds some light on the consequences of punitive control in moral matters. When someone behaves immorally, a psychologist would typically say that the individual has not internalized the moral norm; that is, she may profess that an action is morally wrong, but she has not really taken that information to heart. How can a parent or teacher encourage such internalization? Attribution theories have been quite influential in how psychologists think about this matter. These theories hold that a parent should NOT ensure moral behavior through the use of harsh or punitive measures. Doing so will gain compliance because the child will want to avoid punishment, but the child will not internalize the norm. He will attribute his "good" behavior not to his own belief in the moral precept, but to the desire to avoid punishment. That theory would predict, then, that once the threat of punishment is removed, these children will engage in the forbidden behavior. That prediction is born out in research. But another prediction of the theory is wrong. If children have not internalized the moral precept, they should feel no shame if they break the rule. But they do feel ashamed. Sana Sheik and Ronnie Janoff-Bulman (2013) sought to resolve this paradox. Their hypothesis: punitive parenting on moral matters does lead children to internalize the moral precept (hence the shame). But it also paradoxically makes children less well equipped to resist temptation (hence the tendency to engage in the immoral behavior). Why would it be harder to resist temptation? Well, imagine that I say to you "Hey, it would probably be better if you didn't think about white bears." The idea of a white bear would flash in your mind, but you'd soon think about something else.  But suppose I said "FOR THE LOVE OF GOD AND ALL THAT IS HOLY, DON'T THINK ABOUT A WHITE BEAR, I BEG OF YOU." By making it such a charged request, I have paradoxically made it harder to not think about a white bear. That's the theory. The experimental data seem to support it, although the logic is a little convoluted. First, subjects were asked to fill out a questionnaire about discipline used by their parents. Responses were used to judge the extent to which parents were punitive about moral matters. (This use of questionnaires is common in this literature.) Second, experimenters asked subjects to write out moral precepts; some subjects wrote about positive precepts (things that you should do) or proscriptive ones (things you should not do). They did this to prime subjects, that is, to get them thinking about these moral issues. They varied the type of precept (positive or proscriptive) because harsh parental control is virtually always directed at moral proscriptions.  Third, they asked subjects to briefly describe the action depicted in some paintings. These paintings (like the one shown at left) are emotionally ambiguous--they are open to a wide range of interpretations. Crucially, subjects in the experiment were also told "Please do NOT use any words related to bad, immoral, undesirable behaviors, intentions, or outcomes (e.g., sneaky)." Here's the idea. subjects who had first been prompted to think about moral proscriptions would be thinking about moral proscriptions when they saw the paintings, but they were told NOT to use those thoughts in describing the paintings. Inhibiting those thoughts would presumably "cost" them--their resources for regulating attention would be somewhat depleted. And that should be especially true for students whose parents were punitive about moral matters because such issues are hyper-charged for them. How could you show that their attentional resources were depleted from the struggle to not think about moral proscriptions?  In the final phase of the experiment, the researchers administered a STROOP task--that's the task in which subjects are asked to name ink colors while refraining from mistakenly saying the color names spelled out. Doing so requires attention regulation, and the more tired you are from inhibiting the immoral descriptions of the paintings, the worse you'll do on the STROOP task. And, as predicted, subjects whose parents were punitive were worse on the STROOP task than subjects whose parents were not. But maybe kids with punitive parents are bad at the STROOP for other reasons. Maybe these just happen to be kids who lack attentional resources. In fact, maybe that's why they often got in trouble, and that's why their parents had to be kind of hard on them. That's why the experimenters also included a condition where subjects were asked to think about positive moral precepts. Without that prime, everyone should find it easier NOT to think about proscriptive morality. And indeed, subjects whose parents were punitive don't have a particular problem with the STROOP in this condition. As I promised, the chain of logic supporting the theory is a bit convoluted. Still, the basic account seem plausible. If further data support the theory, the upshot for parents and teachers would be that harsh responses to moral transgressions won't work. They leave subjects feeling ashamed when they transgress, but paradoxically they make is harder to resist the temptation to transgress. Shikh, S. & Janoff0Bulman, R. (2013). Paradoxical consequences of prohibitions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Advance online publication: doi: 10.1037/a0032278 An experiment is a question which science poses to Nature, and a measurement is the recording of nature’s answer. --Max Planck You can't do science without measurement. That blunt fact might give pause when people emphasize non-cognitive factors in student success and in efforts to boost student success. "Non-cognitive factors" is a misleading but entrenched catch-all term for factors such as motivation, grit, self-regulation, social skills. . . in short, mental constructs that we think contribute to student success, but that don't contribute directly to the sorts of academic outcomes we measure, in the way that, say, vocabulary or working memory do.  Non-cognitive factors have become hip. (Honestly, if I hear about the Marshmallow Study just one more time, I'm going to become seriously dysregulated) and there are plenty of data to show that researchers are on to something important. But are they on to anything that that educators are likely to be able to use in the next few years? Or are we going to be defeated by the measurement problem ? There is a problem, there's little doubt. A term like "self-regulation" is used in different senses: the ability to maintain attention in the face of distraction, the inhibition of learned or automatic responses, or the quelching of emotional responses. The relation among them is not clear. Further, these might be measured by self-ratings, teacher ratings, or various behavioral tasks.  But surprisingly enough, different measures do correlate, indicating that there is a shared core construct (Sitzman & Ely, 2011). And Angela Duckworth (Duckworth & Quinn, 2009) has made headway in developing a standard measure of grit (distinguished from self-control by its emphasis on the pursuit of a long-term goal). So the measurement problem in non-cognitive factors shouldn't be overstated. We're not at ground-zero on the problem. At the same time, we're far from agreed-upon measures. Just how big a problem is that? It depends on what you want to do. If you want to do science, it's not a problem at all. It's the normal situation. That may seem odd: how can we study self-regulation if we don't have a clear idea of what it is? Crisp definitions of constructs and taxonomies of how they relate are not prerequisites for doing science. They are the outcome of doing science. We fumble along with provisional definitions and refine them as we go along. The problem of measurement seems more troubling for education interventions. Suppose I'm trying to improve student achievement by increasing students' resilience in the face of failure. My intervention is to have preschool teachers model a resilient attitude toward failure and to talk about failure as a learning experience. Don't I need to be able to measure student resilience in order to evaluate whether my intervention works? Ideally, yes, but that lack may not be an experimental deal-breaker. My real interest is student outcomes like grades, attendance, dropout, completion of assignments, class participation and so on. There is no reason not to measure these as my outcome variables. The disadvantage is that there are surely many factors that contribute to each outcome, not just resilience. So there will be more noise in my outcome measure and consequently I'll be more likely to conclude that my intervention does nothing when in fact it's helping. The advantage is that I'm measuring the outcome I actually care about. Indeed, there would not be much point in crowing about my ability to improve my psychometrically sound measure of resilience if such improvement meant nothing to education. There is a history of this approach in education. It was certainly possible to develop and test reading instruction programs before we understood and could measure important aspects of reading such as phonemic awareness. In fact, our understanding of pre-literacy skills has been shaped not only by basic research, but by the success and failure of preschool interventions. The relationship between basic science and practical applications runs both ways. So although the measurement problem is a troubling obstacle, it's neither atypical nor final. References Duckworth, A. L., & Quinn, P. D. (2009). Development and validation of the Short Grit Scale (GRIT–S). Journal of Personality Assessment, 91, 166-174. Sitzmann, T, & Ely, K. (2011). A meta-analysis of self-regulated learning in work-related training and educational attainment: What we know and where we need to go. Psychological Bulletin, 137, 421-442. A lot of data from the last couple of decades shows a strong association between executive functions (the ability to inhibit impulses, to direct attention, and to use working memory) and positive outcomes in school and out of school (see review here). Kids with stronger executive functions get better grades, are more likely to thrive in their careers, are less likely to get in trouble with the law, and so forth. Although the relationship is correlational and not known to be causal, understandably researchers have wanted to know whether there is a way to boost executive function in kids.

Tools of the Mind (Bedrova & Leong, 2007) looked promising. It's a full preschool curriculum consisting of some 60 activities, inspired by the work of psychologist Lev Vygotsky. Many of the activities call for the exercise of executive functions through play. For example, when engaged in dramatic pretend play, children must use working memory to keep in mind the roles of other characters and suppress impulses in order to maintain their own character identity. (See Diamond & Lee, 2011, for thoughts on how and why such activities might help students.) A few studies of relatively modest scale (but not trivial--100-200 kids) indicated that Tools of the Mind has the intended effect (Barnett et al, 2008; Diamond et al, 2007). But now some much larger scale followup studies (800-2000 kids) have yielded discouraging results. These studies were reported at a symposium this Spring at a meeting of the Society for Research on Educational Effectiveness. (You can download a pdf summary here.) Sarah Sparks covered this story for Ed Week when it happened in March, but it otherwise seemed to attract little notice. Researchers at the symposium reported the results of three studies. Tools of the Mind did not have an impact in any of the three. What should we make of these discouraging results? It's too early to conclude that Tools of the Mind simply doesn't work as intended. It could be that there are as-yet unidentified differences among kids such that it's effective for some but not others. It may also be that the curriculum is more difficult to implement correctly than would first appear to be the case. Perhaps the teachers in the initial studies had more thorough training. Whatever the explanation, the results are not cheering. It looked like we might have been on to a big-impact intervention that everyone could get behind. Now we are left with the dispiriting conclusion "More study is needed." Barnett, W., Jung, K., Yarosz, D., Thomas, J., Hornbeck, A., Stechuk, R., & Burns, S.(2008). Educational effects of the Tools of the Mind curriculum: A randomized trial. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23, 299–313. Bedrova, E. & Leong, D. (2007) Tools of the Mind: The Bygotskian appraoch to early childhood education. Second edition. New York: Merrill. Diamond, A. & Lee, K. (2011). Interventions shown to aid executive function development in children 4-12 years old. Science, 333, 959-964. Diamond, A., Barnett, W. S., Thomas, J., & Munro, S. (2007). Preschool program improves cognitive control. Science, 318, 1387-1388. |

PurposeThe goal of this blog is to provide pointers to scientific findings that are applicable to education that I think ought to receive more attention. Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed