Hence, the stereotype for women (in American culture) is that they are not as good at math as men; for older people, that they are more forgetful than the young; and for African-Americans, that they are less proficient at academic tasks. Members of each group do indeed perform worse at that type of task if the stereotype is made salient just before they undertake it (e.g. Appel & Kronberger, 2012).

Why does it happen? Most researchers have thought that the mechanism is via working memory. When the stereotype becomes active, people are concerned that they will verify the stereotype. These fears occupy working memory, thereby reducing task performance (e.g., Hutchison, Smith & Ferris, 2013).

But a new experiment offers an alternative account. Sarah Barber & Mara Mather (2013) suggests that stereotype threat might operate through a mechanism called regulatory fit. That's a theory of how people pursue goals. If the way you conceive of task goals matches the goal structure of the task, you're more likely to do well than if it's a poor fit.

To test this idea, Barber & Mather tested fifty-six older (around age 70) subjects on a combined memory/working memory task. Subjects read sentences, some of which made sense, others which were nonsensical either syntactically or semantically.

Subjects indicated with a button press whether the sentence made sense or not. In addition, they were told to remember the last word of the sentence for as many of the sentences as they could. Task performance was measured by a combined score: how many sentences were correctly identified (sensible/nonsensical) and how many final words were remembered.

Next, subjects read one of two fictitious news articles. The one meant to invoke stereotype threat described the loss of memory due to aging. The control article described preservation of memory with aging.

Then, subjects performed the sentence task again. We would expect that stereotype threat would lead to worse performance.

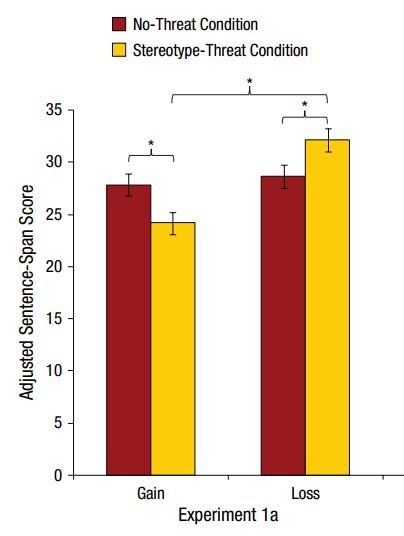

BUT the experimenters also varied the reward structure of the task. Some subjects were told they would get a monetary reward for good performance. Others were told they were starting with a set amount of money, and that each memory error would incur a penalty.

The instructions made a big difference in the outcome. As shown in the graph, framing in terms of costs for errors didn't just remove stereotype threat; it actually lead to an improvement.

This outcome makes sense, according to the regulatory fit hypothesis. Subjects were worried about errors, and the task rewarded them for avoiding errors.

These data are the first to test this new hypothesis as to the mechanism of stereotype threat, and should not be seen as definitive.

But if this new explanation holds up (and if it applies to other groups) it should have significant implications for how threat can be avoided.

References:

Appel, M., & Kronberger, N. (2012). Stereotypes and the achievement gap: Stereotype threat prior to test taking. Educational Psychology Review, 24(4), 609-635.

Barber, S. J., & Mather, M. (2013). Stereotype Threat Can Both Enhance and Impair Older Adults’ Memory. Psychological science, published online Oct. 22, 2013. DOI: 10.1177/0956797613497023.

Hutchison, K. A., Smith, J. L., & Ferris, A. (2013). Goals Can Be Threatened to Extinction Using the Stroop Task to Clarify Working Memory Depletion Under Stereotype Threat. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 4(1), 74-81.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed