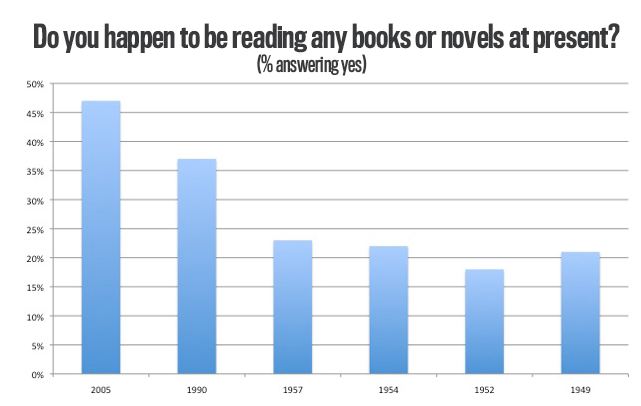

All of the postings I've seen have apparently taken this conclusion at face value, so it seems like it's worth going through why this conclusion is not justified.

First, lots of stuff happened between 1949 and 2005. For example, household income increased for middle- and high-income families. It could be that the internet has negatively affected book reading, but a number of other factors have increased it, so overall we see an increase. The idea that other factors are having a big impact on reading seems legitimate, given the big increase in reading from 1957 to 1990, a year in which very few people had internet access. So perhaps those factors are continuing to boost reading, despite the negative impact of the internet.

The type of analysis we're being asked to perform implicitly is a variety of time series analysis. It's useful in situations where one can't conduct an experiment with a control group. For example, I might track classroom behavior daily for one month using a scale that runs from 1-10. I find that it ranges from 4 to 6 every day. The teacher implements a new classroom management scheme, and from that day forward, classroom behavior ranges from 7 to 9 every day.

Interpreting the new classroom management scheme as the cause of the change is still not certain--some outside-of-class-factor could have just happened to have occurred on that same day that prompted the change in classroom behavior. But the fact that the change in behavior happened over such a narrow time window makes us more confident that such a coincidence is unlikely.

And of course it helps my confidence that it's the same class. In the chart above, we're looking at events that happened over years, with different people who we hope had similar characteristics.

To really get at the effect of the internet on reading habits, you need more finely controlled data. A number of studies were done in the 1950s, examining the effect of television on reading habits. The best of these (see Coffin, 1955) measured reading habits in a city that did not have a television station but was poised to get one, and then measured reading habit again after people in the city had access to television. (The results showed an impact on reading, especially light fiction. Newspaper reading was mostly unaffected, as television news was still in its infancy. Radio listening took a big hit.)

Second, we might note that the most recent year on the chart is 2005. According to the Pew Internet and American Life Project, only 55% of Americans had internet access at that point, and only 30% had broadband. So perhaps the negative impact wouldn't be observed until more people had internet access.

This brings us to more serious studies of whether use of the Internet displaces other activities. The studies I know of (e.g., Robinson, 2010) conclude that Internet use does not displace other activities, but rather enhances them. The data are actually a bit weird--IT use is associated with more of everything: more leisure reading, more newspaper reading, more visits to museums, playing music, volunteering, and participating in sports.

The obvious explanation would be that heavy IT users have higher incomes and more leisure time, but the relationships held after the author controlled for education, age, race, gender, and income--though most of these effects were much attenuated.

This research is really just getting going, and I don't think we're very close to understanding problem.

In sum, the question of what people do with their leisure time and how one activity influences another is complicated. One chart will not settle it.

Coffin, T. E. (1955) Television's impact on society. American Psychologist, 10, 630-641.

Robinson, J. P. (2011) Arts and leisure participation among IT users: Further evidence of time enhancement over time displacement. Social Science Computer Review, 29, 470-480.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed