How do you know that whether a book is at the right level of difficulty for a particular child? Or when thinking about learning standards for a state or district, how do we make a judgment about the text difficulty that, say, a sixth-grader ought to be able to handle?

It would seem obvious that an experienced teacher would use her judgment to make such decisions. But naturally such judgments will vary from individual to individual. Hence the apparent need for something more objective. Readability formulas are intended as just such a solution. You plug some characteristics of a text into a formula and it combines them into a number, a point on a reading difficulty scale. Sounds like an easy way to set grade-level standards and to pick appropriate texts for kids.

Of course, we’d like to know that the numbers generated are meaningful, that they really reflect “difficulty.”

Educators are often uneasy with readability formulas; the text characteristics are things like “words per sentence,” and “word frequency” (i.e., how many rare words are in the text). These seem far removed from the comprehension processes that would actually make a text more appropriate for third grade rather than fourth.

To put it another way, there’s more to reading than simple properties of words and sentences. There’s building meaning across sentences, and connecting meaning of whole paragraphs into arguments, and into themes. Readability formulas represent a gamble. The gamble is that the word- and sentence-level metrics will be highly correlated with the other, more important characteristics.

It’s not a crazy gamble, but a new study (Begeny & Greene, 2014) offers discouraging data to those who have been banking on it.

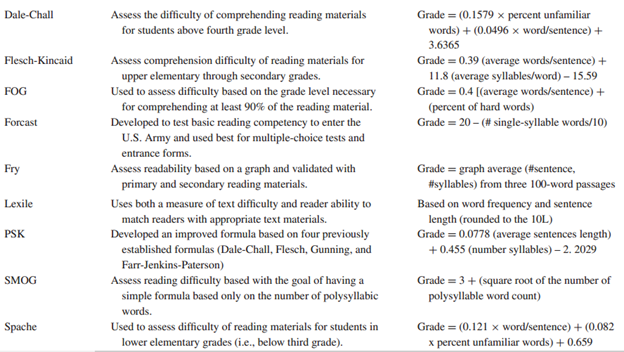

The authors evaluated 9 metrics, summarized in this table:

In this experiment, second, third, fourth, and fifth graders each read six passages taken from the DIBELS test: two passages each from below, at, and above their grade level, for a total of six passages.

Previous research has shown that the various readability formulas actually disagree about grade levels (e.g., Ardoin et al, 2005). In this experiment, oral reading fluency was to referee the disagreement. Suppose that according to PSK, passage A is appropriate for second graders and passage B is appropriate for third graders. Meanwhile Spache says both are third-grade passages. If oral reading fluency is better for passage A than passage B, that supports the PSK. (“Faster” was not evaluated only in absolute terms, but accounted for the standard error of the mean).

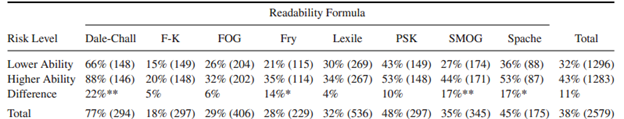

The researchers used an analytic scheme to evaluate how good a job each metric did of predicting the patterns of student oral reading fluency. Each prediction was considered binary: the grade level assignment predicted that there should be a difference (or not) in oral reading fluency: was a difference observed? Chance, therefore, would be 50%. The data are summarized in the Table

So (excepting the Dale-Chall), this study offers no evidence that standard readability formulas provide reliable information for teachers as they select appropriate texts for their students. As always, one study is not definitive, least of all for a broad and complex issue. This work ought to be replicated with other students, and with outcome measures other than fluency. Still, it contributes to what is, overall, a discouraging picture.

References

Ardoin, S. P., Suldo, S. M., Witt, J., Aldrich, S., & McDonald, E. (2005). Accuracy of readability estimates’ predictions of CBM performance. School Psychology Quarterly, 20, 1 – 22.

Begeny, J. C., & Greene, D. J. (2014). Can readability formuas be used to successfully gauge difficulty of reading materials? Psychology in the Schools, 51(2), 198-215.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed