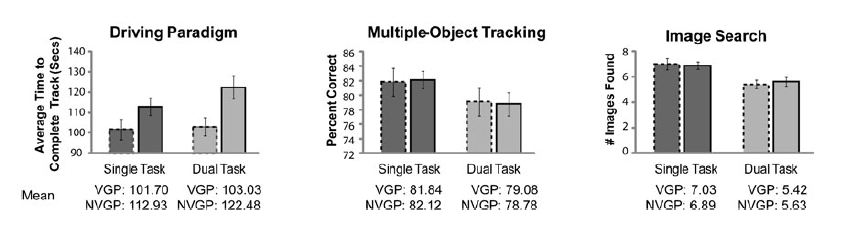

In one (Donohue, James, Eslick & Mitroff, 2012) the authors compared 19 college-aged students who were avid gamers to students with no gaming experience (N = 26). Subjects completed three tasks: a simulated driving game, an image search task (finding simple objects in a complex drawing) and a multiple-object-tracking task. In this task, a number of black circles appear on a white screen. Four of the circles flash for two seconds, and then all of the circles move randomly. At the end of 12 seconds the subject must identify which of the circles flashed.

Subjects performed all three tasks twice: on its own, and with a distracting task (answering trivia questions) performed simultaneously. The question is whether the performance on the experienced gamers would be less disrupted by the attention-demanding trivia task.

These researchers found they were not, as shown in the figure below (click for larger image).

But a different group of researchers found just the opposite.

Strobach, Frensch & Schubert (2012) used much simpler tasks to compare 10 gamers and 10 non-gamers. They used simple reaction time tasks; the subject sat before a computer, and listened over headphones for a tone. When it sounded, the subjects was to push a button as fast as possible. A second task used a visual signal on the screen instead of a tone. In the attention-demanding dual task version, either an auditory or a visual signal might appear, with different responses for each.

In this experiment, gamers responded faster than non-gamers overall, but most important, their performance suffered less in the dual-task situation.

The authors didn't leave it at that. They recognized that the experimental paradigm they used has a significant drawback; they can't attribute the better attention-sharing skills to gaming, because the study is correlational. For example, it may be that some people just happen to be better at sharing attention, and these people are drawn to gaming because this skill makes them better at it.

To attribute causality to gaming, they needed to conduct an experiment. So the experimenters turned some "regular folk" into gamers by having them play an action game (Medal of Honor) for 15 hours. Control subjects played a puzzle game (Tetris) for 15 hours. Subjects improved their dual-task performance after playing the action the game. The puzzle game did not have that effect.

So what is the difference between the two studies?

It's really hard to say. It's tempting to place more weight on the study that found the difference between gamers and non-gamers. Scientists generally figure that if you unwittingly make a mistake in the design or execution of a study, that's most likely to lead to null results. In other words, when you don't see an effect (as in the first study) it might be because there really is no effect, or it might just be that something went wrong.

But then again, the first study has more of what scientists call ecological validity--the tasks used in the laboratory look more like the attention-demanding tasks we care about outside of the laboratory (e.g., trying to answer a passenger's question while driving).

It may be that both studies are right. Gaming leads to an advantage in attention-sharing that is measurable with very simple tasks, but that is washed out and indiscernible in more complex tasks.

The conclusion, then, is a little disheartening. When it comes to the impact of action gaming on attention sharing, it's probably too early to draw a conclusion.

Science is hard.

Donohue, S. E., James, B., Eslick, A. N. & Mitroff, S. R. (2012). Cognitive pitfall! Videogame players are not immune to dual-task costs. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 74, 803-809.

Stroback, T., Frensch, P. A., & Schubert, T. (2012). Video game practice optimizes executive control skills in dual-task and task switching situations. Acta Psychologica, 140, 13-24.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed