Since then I’ve written a couple of articles about learning styles (here and here), created a video on the subject, and put an FAQ on my website. Last week I was on the Science Friday radio program (With Kelly Macdonald and Lauren McGrath) to talk about learning styles and other neuromyths.

I put energy into dispelling the learning styles myth because I thought that audience of educators was representative—that is, that most teachers think the theory is right. But with the exception of one recent study showing that academics often invoke learning styles theories in in professional journal articles (Newton, 2015) there haven’t been empirical data on how widespread this belief is in the US.

Now there are.

Macdonald, McGrath, and their colleagues conducted a survey to test the pervasiveness of various beliefs about learning among American adults (N = 3,048), and among educators in particular (N =598). Similar surveys have been conducted in parts of Europe, East Asia, and Latin American, where researchers have observed high levels of inaccurate beliefs on these issues.

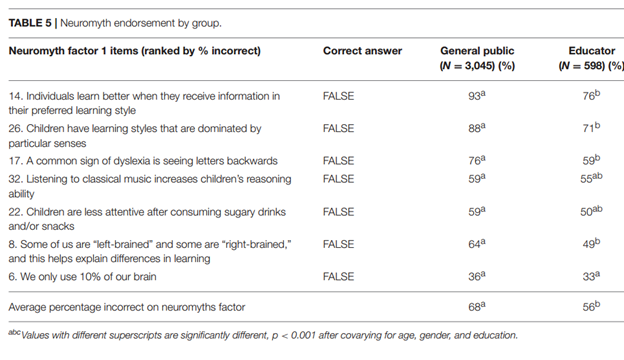

Learning styles theory was endorsed by 93% of the public, and 76% of educators. Data regarding other neuromyths (common misperceptions about learning or the brain) are shown in the table below (from the paper).

Why is acceptance of the idea so high? No one really knows, but here’s my tripartite guess.

First, I think by this point it’s achieved the status of one of those ideas that “They” have figured out. People believe it for the same reason I believe atomic theory. I’ve never seen the scientific papers supporting it (and wouldn’t understand them if I had) but everyone believes the theory and my teachers taught it to me, so why would I doubt that it’s right?

Second, I think learning styles theory is widely accepted because the idea is so appealing. It would be so nice if it were true. It predicts that a struggling student would find much of school work easier if we made a relatively minor change to lesson plans—make sure the auditory learners are listening, the visual learners are watching, and so on.

Third, something quite close to the theory is not only right, it’s obvious. The style distinctions (visual vs. auditory; verbal vs. visual) often correspond to real differences in ability. Some people are better with words, some with space, and so on. The (incorrect) twist that learning styles theories add is to suggest that everyone can reach the same cognitive goal via these different abilities; that if I’m good with space but bad with words (or better, if I prefer space to words), you can rearrange a verbal task so that it plays to my spatial strength.

That’s where the idea goes wrong wrong. First, the reason we make the distinction between types of tasks is that they are separable in the brain and mind; we think verbal and visual are fundamentally different, not fungible. Second, while there are tasks that can be tackled in more than one way, these tasks are usually much easier when done in one way or another. For example, if I give you a list of concrete nouns, one at a time, and ask you to remember them you could do this task verbally (by repeating the word to yourself, thinking of meaning, etc.) or visually (by creating a visual mental image). Even for people who are not very good at imagery, the latter method is a better method of doing the task. Josh Cuevas has an article showing this point coming out early next year: people’s alleged learning styles don’t count for anything in accounting for task performance, but the effect of a strategy on a task are huge.

A final note. I frequently hear from teachers that they learned about the theory in teacher education classes. I've looked at all of the well-known educational psychology textbooks, and none of them present the idea as correct. But neither do they debunk it. Teachers are, according to the survey, more accurate than the general public in their beliefs about learning, but they should be way ahead. Debunking these ideas in ed psych textbooks ought to help.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed