A new report (Brummelman et al, 2013) shows that the consequences of certain praise for kids with low self-esteem can be particularly destructive.

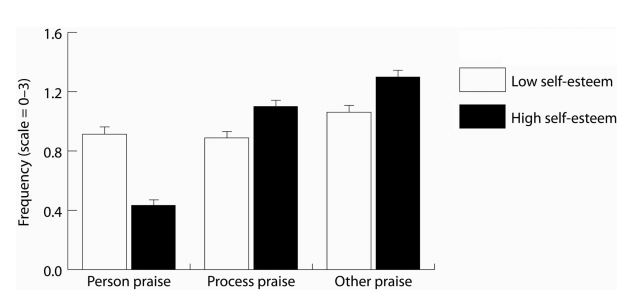

In experiment 1, 357 Dutch-speaking parents (87% mothers) read brief descriptions of children, some with high self-esteem ("Lisa usually likes the kind of person she is") and some with low ("Sarah is often unhappy with herself.") Parents were asked to describe what they would say in response to something the child was described as having done (e.g., "she has just made a beautiful drawing.")

Responses were coded as praising the child's personal qualities (e.g., "You're such a good drawer") or the child's behaviors (""you did a good job drawing!"), other praise (e.g., "beautiful!") or no praise.

Experiment 2 examined whether children with high or low self-esteem respond differently to person praise.

313 children (mean age about 10.5 yrs) completed a standard measure of self-esteem. Several days later at their school, they performed a computer task that (they were told) pitted them against an opponent from another school to see who had faster reactions. They were told that a webmaster would monitor the competitors' performance. (In fact, there was no competitor or webmaster; everything was controlled by the computer.)

After a practice round the webmaster gave either process praise ("wow, you did a great job!"), person praise ("wow, you're great!") or no praise to the subject.

Next, the subject played against their "opponent" and were told that he or she won or lost.

Finally, subjects were asked to rate "how you feel, right now" by agreeing or disagreeing with adjectives like "ashamed," and "humiliated." (They had made similar ratings before the game.)

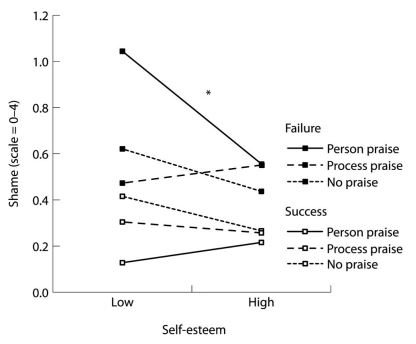

As you would expect, the students who were told they won (the open figures in the graph) didn't feel much shame. Students told they lost (closed figures) felt more.

In addition, the students receiving person praise feel more shame, overall, but crucially, all of this effect is due to the students with low self esteem. They are represented by that highest point on the graph at the upper left.

The effect size is pretty substantial--around d = .5

So it seems that the person praise makes the children with low-self-esteem feel more invested in the game, more like they have something at stake. So when they lose, they feel more shame. The high-self esteem students, in contrast, shrug off the loss, even after the person praise because they generally feel more secure about their abilities.

The message, coupled with the result from Experiment 1, is that adults are biased to do exactly the wrong thing--try to "buck up" kids with low-self esteem by offering person praise ("you're a great kid!") when these children will actually suffer more after a failure if they have received this praise.

The interpretation hangs together, to my mind, but I'd like to see this effect replicated. In particular, the measure of shame seemed heavy-handed. As far as I can tell, students were not asked about other feelings, just those related to shame, so there is a really chance that demand characteristics played a role. (That is, that students were reacting as they thought the experimenter expected them to, not necessarily as they felt.)

Still, an interesting, possibly important experiment.

Reference: Brummelman, E., Thomaes, S., Overbeek, G., Orobio de Castro, B., van den Hout, M. A., & Bushman, B. J. (2013). On Feeding Those Hungry for Praise: Person Praise Backfires in Children With Low Self-Esteem. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. Advance online publication: doi: 10.1037/a0031917

RSS Feed

RSS Feed