Last week I discussed the case Carl Wieman made that education research and physics have more in common than people commonly appreciate. I mentioned in passing Wieman’s suggestion that random control trials—often referred to as the “gold standard” of evidence—are not the be-all and end-all of research, and that qualitative research contributes too. But I didn’t say how it contributes, and neither did Wieman (at least in the paper I discussed). Here, I offer a suggestion.

Qualitative research is usually contrasted with quantitative research. In quantitative research the dependent variable—that is, the outcome—is measured as a quantity, usually using a measurement that is purportedly objective. In qualitative research, the outcome is not measured as a quantity, but as a quality.

For example, suppose I’m curious to know what students think about their school’s use of technology. In a quantitative study, I might develop a questionnaire that solicits student’s opinions about, say, the math and reading software they’ve been using, and also asks students to compare them to the paper versions they used last year. I’d probably try to get most or all of the students in the school to respond. I would end up with ratings which I can treat as quantitative data.

Or I could do a qualitative study, in which I use focus groups to solicit their opinions. The result of this research is not numeric ratings, but transcripts of what people said. I’d try to find common themes in what was said. Because focus groups are time-consuming, I’d probably talk to just a handful of students.

People who criticize qualitative research treat it as a weak version of quantitative methods. For example, a critic would point out that you can’t trust the results of the focus groups, because I might have, by chance, interviewed students with idiosyncratic views. Another problem is that focus groups are not very objective; responses are a product of the dynamic between the interviewer and the subjects, and among the subjects themselves.

These complaints are valid, or would be if we hoped to treat the focus group results the way we treat the outcomes of other experiments. I suggest we should not.

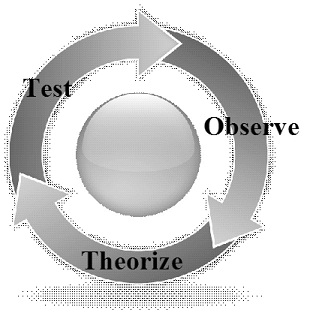

Here’s a simple graphic I used in a book to describe how science works. We begin with observations about the world. These can come from our casual, everyday observations or from previous experiments. We then try to synthesize those observations into a theory; we try to find simplifying rules that describe the many observations we’ve made. This theory can be used to generate a prediction, something we haven’t yet observed, but ought to. Then we test the prediction, and that test leads to a new observation, a new fact about the world. And we continue around the circle, always seeking to refine the theory.

An advantage of qualitative over quantitative data is the flexibility in how its collected. If I want to know what students think of the new technology instruction and I create a quantitative scale to measure it, I’m really guessing that I know the important dimensions of student opinion. I may try to capture their views on effectiveness and ease-of-use, for example, but what students really care about is the fact that so many websites are blocked.

Qualitative studies allow the subject to tell you what he thinks is important. For example in this qualitative study, students suggested that the schools policy on blocking websites affected their relationships with teachers—they felt untrusted. Maybe that’s the kind of thing a researcher would have been looking for, but I doubt it.

In addition, qualitative data tend to be richer. I’m letting the subject describe in his or her own words what she thinks, rather than asking her to select from reactions that I’ve framed.

Naturally, either type of research—qualitative or quantitative--can be poorly conducted. Each has its own rules of the road. It’s important to judge the quality of research by its own set of best-practice rules, and to judge it by how well it fulfils the purpose to which it is suited.

That’s why I believe qualitative research has an undeserved bad reputation. It is judged by standards of quantitative research, and deemed unable to serve purposes that ought to be served by quantitative research. But I agree with Wieman that qualitative research, well-conducted, makes a valuable contribution, one to which quantitative research is ill-suited.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed