But if you have even a minimal knowledge of the field of psychometrics, you know that things are not so simple.

And if you lack that minimal knowledge, Howard Wainer would like a word with you.

The result is an accessible book, Uneducated Guesses, explaining the source of his ire on 10 current topics in testing. They make for an interesting read for anyone with even minimal interest in the topic.

For example, consider the making of a standardized test like the SAT or ACT optional for college applicants, a practice that seems egalitarian and surely harmless. Officials at Bowdoin College have made the SAT optional since 1969. Wainer points out the drawback--useful information about the likelihood that students will succeed at Bowdoin is omitted.

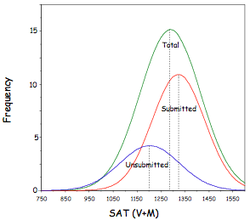

Here's the analysis. Students who didn't submit SAT scores with their application nevertheless took the test. They just didn't submit their scores. Wainer finds that, not surprisingly, students who chose not to submit their scores did worse than those who did, by about 120 points.

So although one might reject the use of a standardized admissions tests out of some conviction, if the job of admissions officers at Bowdoin is to predict how students will fare there, they are leaving useful information on the table.

The practice does bring a different sort of advantage to Bowdoin, however. The apparent average SAT score of their students increases, and average SAT score is one factor in the quality rankings offered by US News and World Report.

In another fascinating chapter, Wainer offers a for-dummies guide to equating tests. In a nutshell, the problem is that one sometimes wants to compare scores on tests that use different items—for example, different versions of the SAT. As Wainer points out, if the tests have some identical items, you can use performance on those items as “anchors” for the comparison. Even so, the solution is not straightforward, and Wainer deftly takes the reader through some of the issues.

But what if there is very little overlap on the tests?

Wainer offers this analogy. In 1998, the Princeton High School football team was undefeated. In the same year, the Philadelphia Eagles won just three games. If we imagine each as a test-taker, the high school team got a perfect score, whereas the Eagles got just three items right. But the “tests” each faced contained very different questions and so they are not comparable. If the two teams competed, there's not much doubt as to who would win.

The problem seems obvious when spelled out, yet one often hears calls for uses of tests that would entail such comparisons—for example, comparing how much kids learn in college, given that some major in music, some in civil engineering, and some in French.

And yes, the problem is the same when one contemplates comparing student learning in a high school science class and a high school English class as a way of evaluating their teachers. Wainer devotes a chapter to value-added measures. I won't go through his argument, but will merely telegraph it: he's not a fan.

In all, Uneducated Guesses is a fun read for policy wonks. The issues Wainer takes on are technical and controversial—they represent the intersection of an abstruse field of study and public policy. For that reason, the book can't be read as a definitive guide. But as a thoughtful starting point, the book is rare in its clarity and wisdom.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed