What are the cognitive consequences of sleep deprivation?

It seems to affect executive function tasks such as working memory. In addition, it has an impact on new learning--sleep is important for a process called consolidation whereby newly formed memories are made more stable. Sleep deprivation compromises consolidation of new learning (though surprisingly, that effect seems to be smaller or absent in young children.)

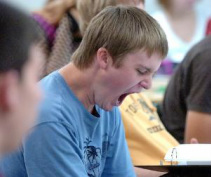

Parents and teachers consistently report that the mood of sleep-deprived students is affected: they are more irritable, hyperactive or inattentive. Although this sounds like ADHD, lab studies of attention show little impact of sleep deprivation on formal measures of attention. This may be because students are able, for brief periods, to rally resources and perform well on a lab test. They may be less able to sustain attention for long periods of time when at home or at school and may be less motivated to do so in any event.

Although these effects are reasonably well established, the cognitive cost of sleep deprivation is less widespread and statistically smaller than I would have guessed. That may be because they are difficult to test experimentally. You have two choices, both with drawbacks:

1) you can do correlational studies that ask students how much they sleep each night (or better, get them to wear devices that provide a more objective measure of sleep) and then look for associations between sleep and cognitive measures or school outcomes. But this has the usual problem that one cannot draw causal conclusions from correlational data.

2) you can do a proper experiment by having students sleep less than they usually would, and see if their cognitive performance goes down as a consequence. But it's unethical to significantly deprive students of significant sleep (and what parent would allow their child to take part in such a study?) And anyway, a night or two of severe sleep deprivation is not really what we think is going on here--we think it's months or years of milder deprivation.

So even though scientific studies may not indicate that sleep deprivation is a huge problem, I'm concerned that the data might be underestimating the effect. To allay that concern, can anything be done to get teens to sleep more?

Another strategy is to maximize the "sleepy cues" near bedtime. The internal clock of teens is not just set for later bedtime, it also provides weaker internal cues that he or she ought to be sleepy. Thus, teens are arguably more reliant on external cues that it's bedtime. So the student who is gaming at midnight might tell you "I'm playing games because I'm not sleepy" could be mistaken. It could be that he's not sleepy because he's playing games. Good cues would be a bedtime ritual that doesn't include action video games or movies in the few hours before bed, and ends in a dark quiet room at the same time each night.

So yes, this seems to be a case where good ol' common sense jibes with data. The best strategy we know of for better sleep is consistency.

References: All the studies alluded to (and more) appear in the article.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed