Students come to school to learn, but that doesn’t mean they begin school devoid of knowledge. As much as policymakers have focused in recent years on the potential richness of the home environment (and the edge that may give children) it’s equally true that children come to school with erroneous beliefs—beliefs that teachers have long recognized can be an obstacle to learning.

That’s especially true in some areas of science. Humans must know how to interact with their world, and that necessity appears to have led to a set of intrinsic, intuitive beliefs about the nature of objects in the world which have some utility for individuals, but also conflict with important principles of biology. Researchers have, in the last ten years or so, documented some of these. A new report (Coley et al, 2017) is perhaps the most thorough in doing so.

Researchers administered a series of measures to three groups of subjects (total N = 211) : 8th grade students, college biology majors, and college non-biology majors. The measures focused three intuitive beliefs:

Anthropocentric thinking: Using humans as the basis for reasoning about other biological species (i.e., thinking of humans as the norm to which others are compared) and seeing humans as biologically unique and discontinuous compared to other species. For example, adults are slower to confirm that plants are living things, consistent with the idea that organisms that seem more distant from humans must not share other qualities with humans.

Teleological thinking: believing that the apparent goal or function of an object or event is the cause of the event. Hence, a young child might reason that lions exist so that they can be in zoos for us to see. An older child might reason that it rains in order that plants grow.

Essentialist thinking: the belief that objects have a fundamental essence that specifies their category membership, and that all members of this category share this essence. For example, an animal is either a bird or not a bird—there’s no degree of “birdiness” in the final analysis, and all birds share the bird essence. Young children believe that parents and their offspring tend to share not only physical characteristics (e.g., eye color) but also preferences (e.g., liking sweets).

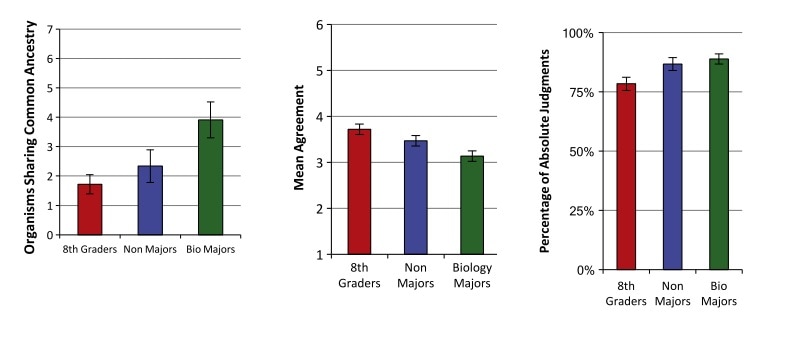

The researchers wanted to examine (1) whether these intuitive beliefs change in late adolescence and (2) whether training in biology affected the prevalence or depth of these beliefs. There was an effect for both factors, but in both cases, smaller than the researchers expected. The graphs below show results for one question type from each category—the final analysis used a composite of questions from each category, but these are representative.

At center, responses to a teleological question. Students read an "explanation" of a biological phenomenon that appealed to causality (e.g., "worms exist to aerate the soil, which benefit plants"). Shorter bars reflect better performance.

At right, responses to an essentialist question. Students were asked questions about absolute category membership (e.g., something is either a mammal or it isn't, and there's never an in-between). Shorter bars reflect better performance.

All in all there are effects of age (and associated effects like further general education) as well as effects of training in biology. But all three groups show the same trend for anthropocentric and teleological thinking. Curiously, essentialist thinking grows stronger with development. The authors suggest a few possible interpretations of this finding the most plausible of which is that it is broadly consistent with how biology is frequently taught.

The core finding---that these intuitive ways of thinking are quite resistant to education—matches the findings regarding naïve physics (e.g., Potvin et al., 2015) and highlights the challenges science teachers face.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed