In that vein, I am following up on a piece I wrote last week, in which I argued that much of the work on this topic in education is neuro-garbage. Most of the piece was devoted to explaining why it's difficult to apply neuroscience to education. (I left it to the reader to infer that it's correspondingly easy to be glib.)

I'll keep things as simple as possible, but fasten your seatbelt if you feel the need.

Neuroscience can give researchers clues about the basic architecture of a cognitive process. It can show that a cognitive process might be more complex than we would have otherwise guessed, or that it's more simple.

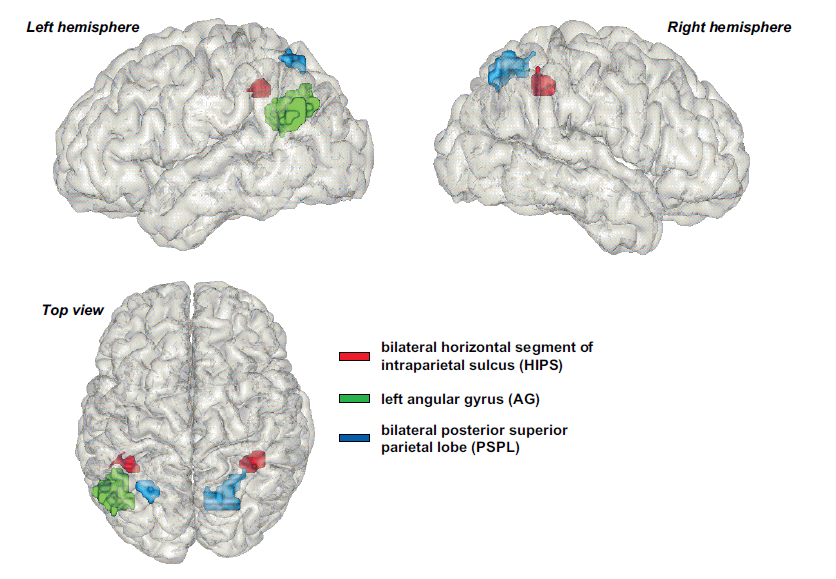

Consider the figure below from Dehaene et al (2003) (click it for a larger version)

Suppose I am an educational psychologist, trying to figure out how children develop concepts of number, and how to coordinate the teaching of early mathematics with these concepts. I must have a theory of how number is represented in the mind. It's possible--actually, it's likely--that I would think of number as one thing, that children have one concept of the number five, for example. But this neuroscientific work indicates that the brain might use three representations of number. So it might be wise for me to use three representations in my cognitive theory of mathematics (which will support my educational theory).

In this example, there is greater diversity (three representations) where we might have guessed that we'd see simplicity (one representation). The opposite may also happen.

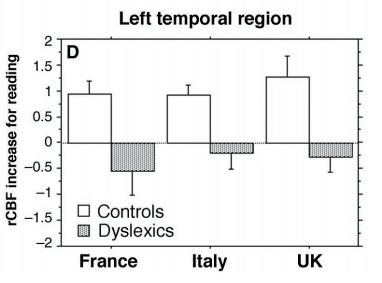

In one example, neuroscientific data were useful in interpreting variations in dyslexia across languages.

One of the peculiarities of dyslexia is that some key symptoms vary across different languages. For example, people with dyslexia usually show a large disparity between visual word recognition and IQ. But that disparity tends to be much larger in languages in which the spelling-sound correspondence is often inconsistent (e.g., English) than in languages where it's more consistent (e.g., Italian).

This pattern raises the question: is what we're calling "dyslexia" really the same thing in English and Italian? Maybe reading difficulties are so intertwined with the language you're learning to read that it doesn't make sense to call problems by the same label when they apply to English vs. Italian. Or maybe the problems kids develop in English-speaking vs. Italian-speaking countries is due to differences in the way reading tends to be taught in different countries.

Eraldo Paulesu and his colleagues (2000) used brain imaging data to argue that dyslexia is the same disorder in readers of different languages. They showed that the same brain region in left temporal cortex shows reduced activation during reading in French, Italian, and British readers who have been diagnosed with dyslexia.

EDIT: It's worth adding that anatomic separability (or overlap) doesn't guarantee cognitive separability or identity. But it's an indicator.

Tomorrow: Method 2.

References:

Dehaene, S., Pizaaz, M., Pinel, P., & Cohen, L. (2003). Three parietal circuits for number processing. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 20, 487-506.

Paulesu, E., Demonet, J.-F., Fazio, F., McCrory, E., Chanoine, V., Brunswick, N., Cappa, S. F., Cossu, G., Habib, M., Frith, C. D., & Frith, U. (2000). Dyslexia: Cultural diversity and biological unity. Science, 291, 2165-2167.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed