How does education fare in this regard?

There is definitely a lot of neuro-garbage in the education market.

Sometimes it's the use of accurate but ultimately pointless neuro-talk that's mere window dressing for something that teachers already know (e.g., explaining the neural consequences of exercise to persuade teachers that recess is a good idea for third-graders).

Other times the neuroscience is simply inaccurate (exaggerations regarding the differences between the left and right hemispheres, for example).

You may have thought I was going to mention learning styles.

Well, learning styles is not a neuroscientific claim; it's a claim about the mind. But it's often presented as a brain claim, and that error is perhaps the most instructive. You see, people who want to talk to teachers about neuroscience will often present behavioral findings (e.g., the spacing effect)--as though they are neuroscientific findings.

What's the difference, and who cares? Why does it matter whether the science that leads to a useful classroom application is neuroscience or behavioral?

It matters because it gets to the heart of how and when neuroscience can be applied to educational practice. And when a writer doesn't seem to understand these issues, I get anxious that he or she is simply blowing smoke.

Let's start with behavior. Applying findings from the laboratory is not straightforward. Why? Consider this question. Would a terrific math tutor who has never been in a classroom before be a good teacher? Well, maybe. But we recognize that tutoring one-on-one is not the same thing as teaching a class. Kids interact, and that leads to new issues, new problems. Similarly, a great classroom teacher won't necessarily be a great principal.

This problem--that collections don't behave the same way as individuals--is pervasive.

That's why we can't take lab findings and pop them right into the classroom. To use my favorite painfully obvious example, lab findings consistently show that repetition is good for memory. But you can't mindlessly implement that in schools--"keep repeating this til you've got it, kids." Repetition is good for memory, but terrible for motivation.

I've called this the vertical problem (Willingham, 2009). You can't assume that a finding at one level will work well at another level.

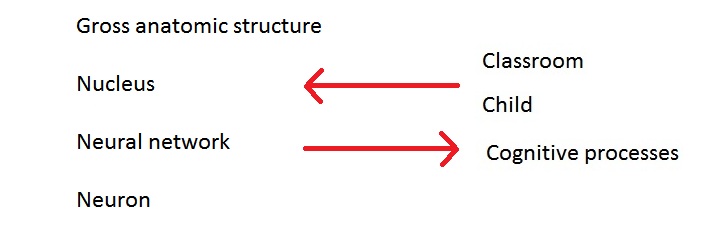

When we add neuroscience, there's a second problem. It's easiest to appreciate this way. Consider that in schools, the outcomes we care about are behavioral; reading, analyzing, calculating, remembering. These are the ways we know the child is getting something from schooling. At the end of the day, we don't really care what her hippocampus is doing, so long as these behavioral landmarks are in place.

Likewise, most of the things that we can change are behavioral. We're not going to plant electrodes in the child's brain to get her to learn--we're going to change her environment and encourage certain behaviors. A notable exception is when we suspect that there is a pharmacological imbalance, and we try to use medication to restore it. But mostly, what we do is behavioral and what we hope to see is behavioral. Neuroscience is outside the loop.

The translation to use neuroscience in education can be done--it has been done--but it isn't easy. (I wrote about four techniques for doing it here, Willingham & Lloyd, 2007).

Now, let's return to the question we started with: does it matter if claims about laboratory findings about behavior are presented as brain claims?

I'm arguing it matters because it shows a misunderstanding of the relationship of mind, brain, and educational applications.

As we've seen, behavioral sciences and neuroscience face different problems in application. Both face the vertical problem. The horizontal problem is particular to neuroscience.

When people don't seem to appreciate the difference, that indicates sloppy thinking. Sloppy thinking is a good indicator of bad advice to educators. Bad advice means that neurophilia will become another flash in the pan, another fad of the moment in education, and in ten year's time policymakers (and funders) will say "Oh yeah, we tried that."

Neuroscience deserves better. With patience, it can add to our collective wisdom on education. At the moment, however, neuro-garbage is ascendant in education.

EDIT:

I thought it was worth elaborating on the methods whereby neuroscientific data CAN be used to improve education:

Method 1

Method 2

Method 3

Method 4

Method 5

Conclusions

Willingham, D. T. (2009). Three problems in the marriage of neuroscience and education. Cortex, 45, 54-545.

Wilingham, D. T. & Lloyd, J. W. (2007). How educational theories can use neuroscientific data. Mind, Brain, & Education, 1, 140-149.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed