It seems obvious that students are, at the least, themselves distracted during lectures--supporting anecdotal evidence can be collected by popping into the back of any large lecture hall and observing laptop content; you'll see plenty of social media websites open, students responding to messages or email, and a surprising number of people shopping.

But most data on the consequences of laptop use are correlational; for example, students who report taking notes on laptops earn lower grades than those who don't, and observational data show that students have non-course related software open during class (e.g., Kraushaar & Novak, 2010). The obvious problem is that laptop use may not be causing low grades; laptop use may be more appealing to those who would earn lower grades anyway.

Two new studies using different methods suggest that laptop use does, indeed, incur a cost to students.

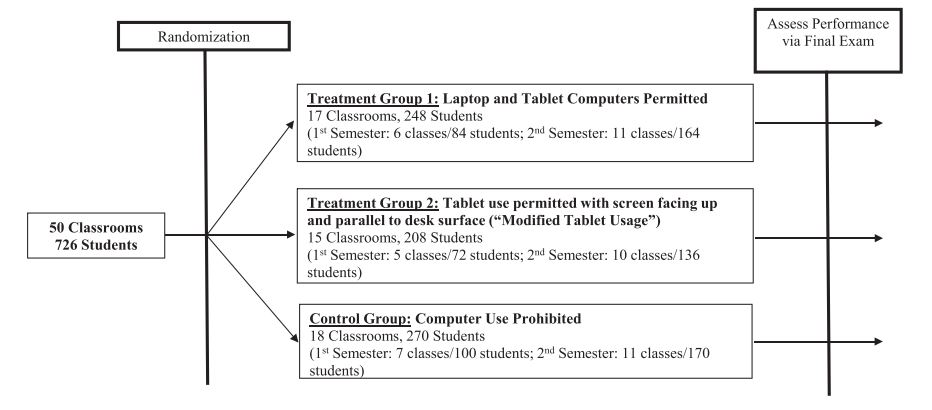

In one (Carter et al., 2017) students in sections of a required introductory economics course were randomly assigned to use a laptop or to refrain from doing so. In a clever twist, some classrooms were asked to take notes on tablets with the tablet lying flat, hence reducing the likelihood that the screen would distract neighboring students.

We can have greater confidence that laptop use is really causal here, given that class sections were randomly assigned to use them or not. But there are some other caveats of interpretation. It's possible that teachers teach differently when they know their students are taking notes on devices. We should also be cautious in generalizing beyond the institution (West Point) and the class (economics). For example, perhaps economics requires the drawing of many figures and graphs, a process that's clumsy on a device. Perhaps the same experiment conducted in an English literature class would show no effect. Or maybe laptop use offers a small benefit to most students, but there's a minority for whom the forced use of a laptop incurs a big cost.

The second study (Patterson & Patterson, 2017) uses a different, complimentary method that avoids these problems (but has others).

The researchers noted that, at their institution, different classes required laptops (15%), forbade them (2%), or made them optional (83%). The researchers reasoned that a student who had a laptop-optional class might be nudged into using one if she had a laptop-required class the same day. After all, she would already have the laptop with her, so why not use it? And indeed, their survey showed that students were about 20% more likely to use a laptop under those circumstances.

And students were 48% less likely to use laptop in a laptop-optional class if they had another class the same day that forbade laptop use.

So researchers compared grades in a class where some students are biased to use laptops and others were biased not to use them--biased, not forced, so if a student believes he really takes better notes on a laptop, he can use it. And both the laptop-user and non-user are in the same class, with the same opportunities to be distracted by other students, and experiencing the same lecture from the professor.

Researchers analyzed about 5,500 grades in lap-top optional courses from undergraduate and masters students over the course of six semesters. All were enrolled at the same liberal arts college.

The effect of having a laptop-required course at another time was d = -.32 to -.46. Having a laptop-prohibited course the same day was associated with a positive effect, d = .14 to .25. (These effects controlled for gender, ethnicity, age, course load, course schedule difficulty, major, and GPA.)

Patterson & Patterson found that the negative effect was larger for weaker students--in fact, there was little or no effect for stronger students. They also found that laptop use (or more precisely, having a laptop-required course the same day) had a larger negative effective in quantitative classes.

So we have two studies--a randomized control trial, and a quasi-experimental design--to add to the correlational studies showing that students are better off taking notes by hand than doing so on a laptop. None is perfect, but different designs have different flaws. This desirable state of affairs is referred to as converging operations--different types of experiments all point to the same conclusion.

In closing, it's worth remembering that this study does not concern all classroom laptop use, but rather one function: taking notes in a lecture course. Still, considering that most time in introductory college courses is spent listening to lectures, the impact of this work ought to be consequential.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed