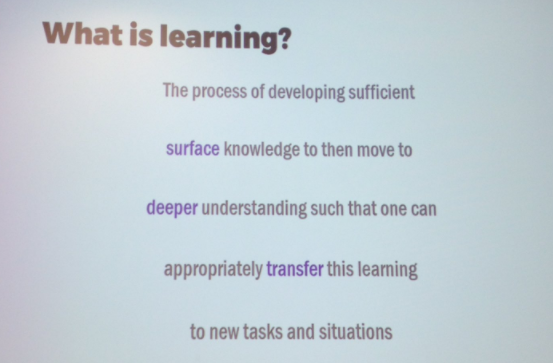

The Twitter thread began when Old Andrew asked whether John Hattie’s definition (shown below) was not “really terrible."

Hattie's definition has two undesirable features. First, it entails a goal (transfer) and therefore implies that anything that doesn’t entail the goal is not learning. This would be….weird. As Dylan Wiliam pointed out, it seems to imply that memorizing one’s social security number is not an example of learning.

The second concern with Hattie’s definition is that it entails a particular theoretical viewpoint; learning is first shallow, and then later deep. It seems odd to include a theoretical perspective in a definition. Learning is the thing to be accounted for, and ought to be independent of any particular theory. If I’m trying to account for frog physiology, I’m trying to account for the frog and it's properties, which have a reality independent of my theory.

The same issue applies to Kirschner, Sweller and Clark's definition, "Learning is a change in long-term memory." The definition is fine in the context of particular theories that specify what long term memory is, and how it changes. Absent that, it invites those questions: “what is long term memory? What prompts it to change?” My definition of learning seems to have no reality independent of the theory, and my description of the thing to be explained changes with the theory.

It’s also worth noting that Kirscher et al’s definition does not specify that the change in long term memory must be long-lasting…so does that mean that a change lasting a few hours (as observed in repetition or semantic priming) qualifies? Nor does their definition specify that the change must lead to positive consequences…does a change in long term memory that results from Alzheimer’s disease qualify as learning? How about a temporary change that’s a consequence of transcranial magnetic stimulation?

I think interest in defining learning has always been low, and always for the same reason: it’s a circular game. You offer a definition of learning, then I come up with a counter-example that fits your definition, but doesn’t sit well with most people’s intuitions about what “learning” means, you revise your definition, then I pick on it again and so on. That's what I've done in the last few paragraphs, and It’s not obvious what’s gained.

The fading of positivism in the 1950s reduced the perceived urgency (and for most, the perceived possibility) of precise definitions. The last well-regarded definition of learning was probably Greg Kimble's in his revision of Hilgard & Marquis’s Conditioning and Learning, written in 1961: “Learning is a relatively permanent change in a behavioral potentiality that occurs as a result of reinforced practice,” a formulation with its own problems.

Any residual interest in defining learning really faded in the 1980s when the scope of learning phenomena in humans was understood to be larger than anticipated, and even the project of delineating categories of learning turned out to be much more complicated than researchers had hoped. (My own take (with Kelly Goedert) on that categorization problem is here, published in 2001, about five years after people lost interest in the issue.)

I think the current status of “learning” is that it’s defined (usually narrowly) in the context of specific theories or in the context of specific goals or projects. I think the Kirschner et al were offering a definition in the context of their theory. I think Hattie was offering a definition of learning for his vision of the purpose of schooling. I can't speak for these authors, but I suspect neither hoped to devise a definition that would serve a broader purpose, i.e., a definition that claims reality independent of any particular theory, set of goals, or assumptions. (Edit, 6-28-17. I heard from John Hattie and he affirmed that he was not proposing a definition of learning for all theories/all contexts, but rather was talking about a useful way to think about learning in a school context.)

This is as it should be, and neither definition should be confused with an attempt at a all-purpose, all-perspectives, this-is-the-frog definition.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed