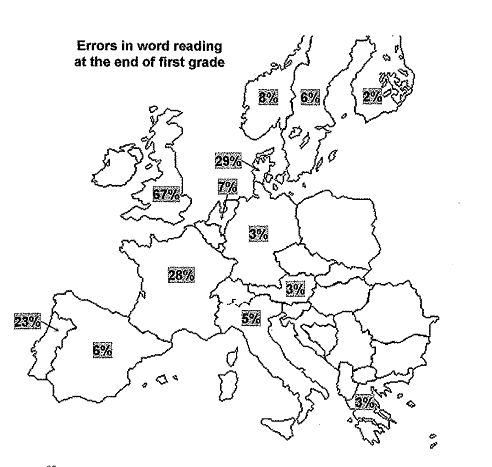

Countrywide differences in instruction could play a role, but Dehaene emphasize that the countries in which children make a lot of errors--Portugal, France, Denmark, and especially Britain--just happen to have deeper orthographies.

A shallow orthography means that there is a straightforward correspondence between letters and phonemes. English, in contrast, has one of the deepest (most complex) orthographies among the alphabetic languages: for example, the letter combination "gh" if pronounced differently in in "ghost," "eight," and "enough."

In short, children learning to read English have a difficult task in front of them--and so too, therefore, do teachers.

Is there a lesson to be drawn here?

To me, the difficult orthography of English highlights the importance of careful sequencing in the learning of grapheme-phoneme pairs, along with a limited number of sight words--sequencing that exploits the regularities that exist, and bring children as swiftly as possible to the point that they can read texts and so feel a sense of accomplishment.

In Italy, for example, the order in which grapheme-phoneme pairs are taught would matter much less because there simply is not that much to learn. Several months of instruction is sufficient for most children to reach a point that they can decode most texts.

The deep orthography of English also sheds light on why American schools spends as much time on English-language arts (ELA) as they do: something like two-third of instructional time in the first grade (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2002).

One might draw the conclusion that the difficulty of the task in reading requires enormous amounts of time. Another point of view--one I share--is that this practice places too much emphasis on ELA at the expense of other content, and runs a high risk of discouraging kids who might become passionate about science, or history, or geography, but won't because the early elementary years contain so little content beyond ELA and mathematics.

I think it would worth our accepting slower progress in reading in exchange for broader subject-matter coverage in early grades--coverage that will actually pay dividends for reading comprehension in later grades.

Dehaene, S. (2009). Reading in the Brain. New York: Viking.

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network (2002). The Relation of Global First-Grade Classroom Environment to Structural Classroom Features and Teacher and Student Behaviors. The Elementary School Journal, 102, 367-387

Seymour, P. H. K., maro, M., & Erskine, J. M. (2003). Foundation literacy acquisition in European orthographies. British Journal of Psychology, 94, 143-174.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed