- Asking students to answer questions about a text before they read it makes memory for that content better. Why?

- True or False: Prequestions usually exact a cost to content that students read which was not prequestioned.

The interpretation of this phenomenon is straightforward: posing questions keys the reader’s attention to certain content, and they pay less attention to everything else. Indeed, when researchers put in boldface type information in the text that was not prequestioned, but would later appear on the test, the disadvantage vanished (Richland et al, 2009). The boldface drew attention to the content that would have otherwise been skimmed.

In some cases, the teacher may view that as a worthwhile tradeoff, but that’s probably infrequent—she’d prefer the boost to X, Y, and Z occur without the cost.

A new paper (Carpenter & Toftness, 2017) may suggest a strategy to avoid the problem, although the experiment actually tested memory for video content.

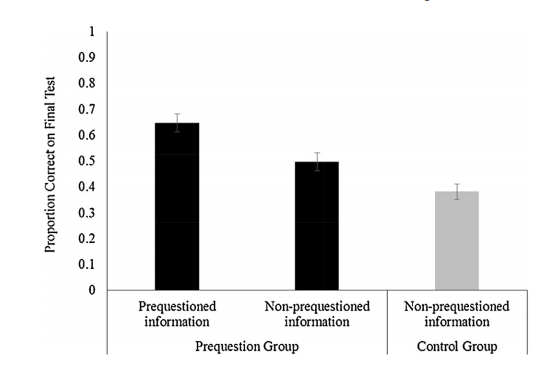

The researchers tested 85 undergraduates, each of whom watched a video lasting about eight minutes. The video was divided into three segments describing the original settlement of Easter Island, religious practices there, and the arrival of outsiders. The researchers generated four questions about each segment. Half of the subjects were asked to guess at the answer to two randomly selected questions about the upcoming segment. The control group simply pushed a button to continue on with the video. At the end of the video, subjects in both groups answered all 12 questions about the video in random order.

Just as in prior experiments using text rather than video, asking people about specific information before seeing the video made it more likely they would learn that information once they watched the video. (That’s the tallest bar at far left).

Why was the cost not observed? Carpenter & Toftness emphasize that a reader controls the pace of reading; the reader can skip over content that she deems less important, and read again content that matters more. The viewer does not control the pace of video; important content might pop up at any time, and once it’s past it cannot be reviewed. So the viewer is more likely to attend closely to the whole thing.

The researchers note that this attention hypothesis can help explain other instances in the research literature where the prequestioning deficit for other content is not observed. For example, Pressely et al (1990) asked subjects to rate each paragraph for interest. Little & Bjork (2016) showed that non-prequestioned information got a boost if it was mentioned in a prequestion, although not the target to-be-learned information.

So in the final analysis, can teachers pose prequestions in a way that boosts memory for targeted content but doesn’t incur a cost for everything else?

In principle, yes. With the right type of material (boldfaced, or video), you're good, and asking for interest judgments works too. But of course none of these may be practicable as the teacher envisions the lesson plan.

This work suggests that a teacher could devise another strategy that uses prequestions without cost--a mental task that requires attention to all content, not just the prequestioned would do the trick. True in principle, but the bottom line on prequestions a the moment seems to be “proceed with caution.”

- Asking students to answer questions about a text before they read it makes memory for that content better. Why?

- Name a strategy other than using video content that eliminates the cost to non-prequestioned information from a text.

- True or False: Prequestions usually exact a cost to content that students read which was not prequestioned.

- Do you think textbook authors should pose prequestions before each chapter? Justify your answer.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed